Our Views

How to Plan a Government Information System in 90 Days: The Minimum Viable Roadmap

Government information systems don’t fail because the technology is “too hard.” They fail because the problem isn’t defined, the users aren’t understood, and decisions get delayed until the project turns into a moving target. A 90-day planning window forces discipline: you don’t have time for perfect—you need clear choices, a realistic scope, and a buildable plan.

This article lays out a minimum viable roadmap: the smallest set of steps and outputs that make a government information system bankable, procurable, and implementable—without drowning teams in paperwork.

What “minimum viable roadmap” actually means

A roadmap is not a slide deck with aspirations. It’s a decision tool.

In 90 days, you’re aiming to produce just enough clarity so leadership can approve the direction, budget holders can see the cost drivers, IT can validate feasibility, and procurement can launch a credible tender. If your outputs can’t be used to make decisions, they’re not roadmap outputs—they’re documentation.

The benchmark is simple: at Day 90, you should be able to answer, in plain language, what we’re building, who it’s for, how it will work, what it will cost, how we’ll deliver it, and how we’ll measure success.

The 90-day structure (without the fluff)

Think of the work in four sprints. Each sprint ends with concrete deliverables that reduce risk.

Days 1–10: Align on purpose and authority

Start by locking down the “why” and the “who decides.” This is where many projects quietly break: five agencies share the same system, but nobody owns decisions.

You want a short Project Charter that names the sponsor, the product owner, the governance model, and the decision cadence. Pair that with a crisp problem statement (what is broken today, for whom, and at what cost). If you can’t write it on half a page, you’re not ready to design anything.

Days 11–30: Discover users, processes, and constraints

This sprint is about reality. You map the service as it exists: user journeys, process steps, bottlenecks, and data pain points. The goal is not to document everything—it’s to identify the few moments that drive 80% of delays, complaints, or leakage.

At the end of this sprint you should have validated user journeys, a shortlist of priority use cases, and a clear view of the constraints that will shape the solution: legal obligations, data protection, connectivity limits, legacy systems, and operational capacity.

Days 31–60: Design the “minimum viable system”

Now you translate needs into something buildable. The most important shift here is discipline: your system must deliver a minimum viable service, not every feature every stakeholder wants.

This is where you define functional requirements in a way procurement and vendors can price, while keeping room for iteration. You also decide early whether you’re going build, buy, or configure, and what integrations are non-negotiable. A simple architecture diagram that shows data flows and ownership is often more useful than 40 pages of text.

By Day 60, you want a draft solution blueprint: scope, modules, roles, data model outline, integration needs, security approach, and a realistic operating model for the institution that will run it.

Days 61–90: Turn the plan into something that can be financed and procured

This is where roadmaps become real. You convert the blueprint into a delivery plan: sequencing, resourcing, costs, procurement strategy, and implementation governance.

Crucially, you define what “done” means. If you can’t measure adoption and service quality, you’ll end up measuring only outputs like “number of trainings delivered.” Your Day-90 package should include KPIs, a monitoring approach, and a change management plan that treats adoption as a product feature—not an afterthought.

The deliverables that matter most (and why)

A 90-day roadmap doesn’t need hundreds of pages, but it does need a few high-leverage artifacts:

1) A one-page service narrative.

What the system will do, for whom, and the value it unlocks. This is what senior officials remember and repeat.

2) A “top 10” use-case list with acceptance criteria.

If the system can’t deliver these use cases reliably, it’s not the right system.

3) A data and interoperability note.

Which datasets exist, which don’t, who owns them, and what needs to integrate with what. This prevents expensive surprises later.

4) A security and privacy baseline.

Not a full audit—just clear minimum standards: access control, logging, incident response, hosting requirements, and compliance constraints.

5) A delivery roadmap with costs and procurement route.

Phasing, staffing assumptions, CAPEX/OPEX ranges, and what can be contracted now versus later.

These outputs create bankability because they reduce uncertainty—the main reason public IT procurements attract weak bids or inflated pricing.

Common traps (and how to avoid them)

Trap 1: Trying to digitize chaos.

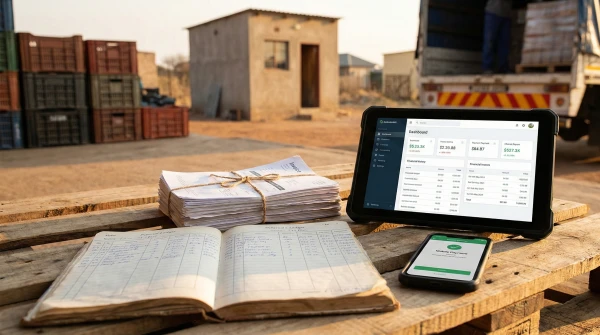

If the underlying process is broken, digitizing it just makes the failure faster. In the 90-day window, focus on “minimum viable process improvement” for the biggest pain points.

Trap 2: Treating stakeholder consultation as consensus-building.

You don’t need everyone to agree—you need everyone to be heard, and a clear authority to decide. Governance is the product’s backbone.

Trap 3: Ignoring the operating model.

A system without a real owner, budget line, support capacity, and data stewardship is a pilot that never scales. Define the institutional home early.

Trap 4: Writing requirements no vendor can price.

Avoid vague language like “modern, robust, user-friendly.” Translate it into measurable requirements: response time, uptime, accessibility standards, audit logs, user roles, reporting needs.

How this looks in practice: a note from Aninver’s experience

Across our digital and public-sector assignments—ranging from maintaining the African Development Bank’s CPIA web platform, to designing digital training and capability-building programs in the Caribbean, to supporting public institutions with web platforms and digital communication tools—the pattern is consistent: projects move faster when teams commit to a minimum viable scope, clear governance, and usable data from day one.

If your institution is planning an information system and wants a roadmap that can actually be procured and implemented, explore more of Aninver’s work and articles on digital transformation and public-sector delivery—where we share practical approaches, lessons learned, and tools that help projects go from intention to execution.