Our Views

AI for Development: Practical Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture and Health

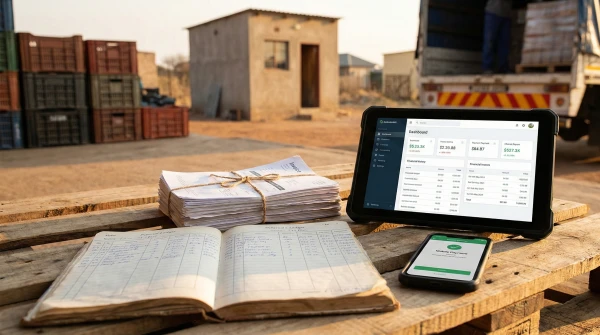

Artificial intelligence is steadily shifting from “innovation initiative” to enabling infrastructure in development. That change matters because it exposes a hard truth: most AI efforts in agriculture and health fail on delivery, not on technology. Models are built faster than institutions can absorb them, data improves slower than project timelines assume, and outputs often land in parallel reporting systems rather than inside the decisions that shape budgets, services, and outcomes.

For investors, public agencies, and C-level leaders, the relevant question is no longer whether AI can work in these sectors. It is whether AI can be made operational—embedded in real workflows with clear accountability—and resilient to the realities of constrained capacity, imperfect data, and shifting priorities. The winners will not be those with the most sophisticated algorithms, but those who treat AI as a capability that needs an operating model: ownership, defensible decision rights, reliable inputs, and a feedback loop that improves performance over time.

From pilot thinking to institutional capability

AI is often procured like a product and managed like a short project. That framing is convenient, but it is strategically misaligned with how value is created. A model that produces insights without changing a decision is not an asset; it is an analytic ornament. Conversely, a modest model that shortens response time, improves targeting, or reduces administrative load can generate outsized returns because it changes behaviour inside the system.

That is why “scale” should be defined cautiously. Scaling is not extending a dashboard to more districts or facilities; it is the ability to reproduce better decisions under real-world stress: staff turnover, patchy connectivity, incomplete registries, political sensitivity around resource allocation, and the slow grind of public procurement. When AI fails to scale, it is often because these constraints were treated as implementation details rather than design inputs.

Agriculture: value emerges where decisions meet variability

Agriculture is a natural environment for AI because it is a business of volatility. Weather shocks, pest pressure, soil heterogeneity, and market fluctuations interact in ways that make blanket advice and uniform programs blunt instruments. AI’s promise is to reduce that bluntness by introducing precision—targeting resources and interventions where marginal impact is highest. The practical test is whether the tool improves the decisions made by extension systems, agribusiness operators, and public programs, not whether it produces an impressive model card.

Early warning systems are a good example. Remote sensing, weather feeds, and field reporting can identify anomalies before losses become locked in—whether that is vegetation stress, drought risk, or conditions conducive to outbreaks. Yet the strategic constraint is not detection; it is response capacity and funded playbooks. If alerts do not arrive through channels that field teams actually use, or if they do not translate into feasible actions, the system accelerates awareness without improving outcomes.

The same logic applies to agronomic advice. Many countries face structural limits in extension coverage and uneven consistency in the guidance farmers receive. AI can support more uniform recommendations and more adaptive advice, but it is most credible when it augments frontline teams rather than attempting to replace them. In practice, adoption improves when decision support tools are designed as workflow companions—helping agents prioritize, standardize, and learn from field feedback—so extension becomes more scalable and accountable.

Where programs and financing intersect—subsidies, input distribution, irrigation investments, blended finance—AI can increase both effectiveness and legitimacy, but the governance bar rises sharply. Better targeting can reduce leakage and improve value-for-money, yet the political economy is unforgiving: if selection criteria are opaque, communities will challenge them; if models are unauditable, agencies will hesitate to use them. In these cases, governance is the product, and the model is only a component of a broader decision system.

Financial services in agriculture illustrate a similar trade-off. AI can help lenders and insurers interpret risk where traditional data is thin, by combining climate histories, production proxies, and operational information to support underwriting. But access expands only if decisions are explainable to both loan officers and customers. In rural markets, trust is a primary asset, and a black-box decision that cannot be defended will be quietly ignored even if it is statistically strong.

Health: the strongest returns come from reducing system load

Health systems, particularly in emerging markets, face high demand, workforce shortages, uneven data, and pressure to deliver consistent quality under stress. In this environment, AI tends to create value when it reduces cognitive and administrative load, strengthens adherence to protocols, and improves the speed at which systems detect and respond to risk. The highest ROI use cases are often operational, not futuristic.

Clinical decision support and triage tools can help standardize care pathways in primary facilities where guidelines are complex and supervision is thin. The design posture matters. Tools framed as replacing clinical judgment are resisted; tools framed as structured assistance are adopted. In practice, credibility comes from transparency—showing why a pathway is suggested and what information is missing—while keeping accountability with clinicians and facility leadership.

Diagnostic support in imaging offers another pragmatic route, especially where specialist capacity is scarce. AI can prioritize cases for review and reduce bottlenecks, but the strategic constraint often lies outside the tool: referral pathways, treatment capacity, and the ability to act on flagged risk. Detection without response capacity creates frustration and reputational risk, as expectations rise faster than services.

Public health surveillance and outbreak detection have similar dynamics. AI can accelerate pattern recognition across routine data streams, but speed only matters if there is a defined response architecture: who receives alerts, who validates, and who has authority to mobilize action. The performance metric that matters is not model accuracy in the abstract; it is time saved to decision and action.

Supply chain forecasting is often less glamorous but can be more scalable in impact. Medicine stock-outs commonly reflect weak forecasting, fragmented procurement, and operational blind spots rather than absolute scarcity. AI can improve demand estimation and distribution planning, but success hinges on reliable data pipelines and disciplined operating routines. Leaders who treat this as an operational capability—integrated into replenishment decisions and iterated over time—often see more tangible gains than those who start with broad “AI platforms.”

The delivery agenda that separates signal from theatre

Across agriculture and health, the same execution pattern repeats: the most successful deployments begin with a decision that matters and can be measured. They engineer a complete loop—inputs, recommendations, action, and feedback—so the model is not an endpoint but a component inside a system that learns. They treat data as an operational asset rather than a prerequisite that must be perfect before anything starts. The differentiator is not intelligence; it is operationalization.

Procurement is where many programs either become investable or become fragile. Buying “an AI solution” is an easy tender to write and a hard one to make effective. Procuring outcomes—reduced stock-outs, improved targeting accuracy, faster response times, better coverage—forces bidders to demonstrate workflow integration, maintenance plans, and capacity transfer. It also helps investors and DFIs judge durability: an AI tool that cannot be owned, managed, and audited locally is not a long-term asset.

Ultimately, AI in development should be treated as a governance-and-delivery challenge with a technology component, not the other way around. The strategic upside is compelling: better targeting in resource-constrained environments, earlier visibility of risks, and more consistent service delivery. But that upside materializes only when AI is structured as an institutional capability—designed for accountability and funded to operate beyond the pilot phase.

Navigating these complexities requires more than technical enthusiasm; it demands market intelligence, sector judgment, and delivery discipline that connects design choices to procurement, financing, and operational reality. At Aninver, we help clients translate AI ambition into delivery-ready programs—grounded in workflow analysis, data and governance design, and practical pathways to scale. For more on how we approach digital solutions in development contexts, explore our Projects section on aninver.com or reach out to discuss how an AI use case can be positioned as an investable, implementable program.