Our Views

Access to Finance for SMEs: Breaking Down Barriers to Business Growth in Developing Countries

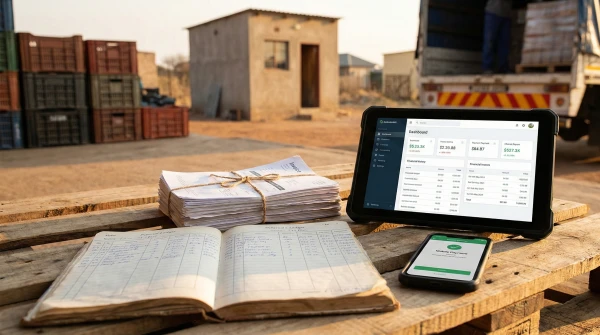

Small and medium-sized enterprises sit at the centre of most developing economies, yet they operate with a structural handicap: the financial system often prices them as risk before it sees them as opportunity. This is not simply a matter of scarce capital. It is the cumulative effect of information gaps, weak collateral regimes, high transaction costs, and regulatory choices that—sometimes unintentionally—tilt finance toward the largest and most formal firms. The result is a familiar development paradox: SMEs are expected to drive jobs, productivity, and resilience, while being denied the oxygen required to scale.

For policymakers and investors, the stakes are increasing. Macroeconomic volatility, climate impacts, and geopolitical fragmentation are forcing businesses to adapt faster, hold more working capital, and invest in operational resilience. At the same time, governments are under pressure to deliver jobs and broaden tax bases without expanding public payrolls. SME finance is therefore not a niche inclusion agenda; it is a competitiveness agenda. The question is not whether to expand access, but how to do so in a way that is commercially sustainable, fiscally disciplined, and institutionally credible.

Why SME financing fails in practice

The “financing gap” is often described as a shortage of liquidity, but the bottleneck is more precise: banks struggle to underwrite SMEs efficiently and defensibly. Many SMEs have thin financial records, cash-based operations, and volatile revenues linked to seasonality or commodity prices. That makes traditional credit assessment costly, and in markets where legal enforcement is slow, the expected recovery value of collateral is low. When lenders cannot price risk accurately, they ration credit. When they ration credit, the market looks like scarcity—even when liquidity exists elsewhere in the system.

Informality amplifies this dynamic. Informal firms may be rationally avoiding taxes or regulatory burdens, but they are also opting out of the data trails that finance depends on. The issue is not moral; it is mechanical. Without verifiable information, lenders substitute collateral and conservative assumptions for business potential. This is why “train SMEs to write business plans” rarely moves the needle on its own. Unless underwriting costs fall and recovery prospects improve, the supply curve of SME credit remains stubborn.

There is also a macro layer that is often overlooked. In many developing countries, banks earn attractive risk-adjusted returns by holding government paper or lending to a narrow set of top-tier corporates. In that environment, SME lending must compete against alternatives that are simpler, safer, and cheaper to administer. If the incentive structure of the financial sector is not addressed, SME finance will remain a policy aspiration rather than a market outcome.

The real barriers: risk, cost, and trust

Credit risk is only one component of the problem. For SMEs, the cost of borrowing reflects not just default probability but the cost of servicing small loans. Origination, due diligence, monitoring, and collections are expensive relative to ticket size, especially in fragmented geographies. Even where interest rates are capped or subsidised, lenders will respond by tightening eligibility or reducing exposure, because margins do not cover operational costs. Efficiency, not generosity, is the scalable route to lower SME borrowing costs.

Trust is the other barrier. SMEs often perceive banks as slow, unpredictable, and collateral-obsessed, while banks perceive SMEs as opaque and difficult to manage. This mutual scepticism shapes behaviour: SMEs under-report; banks over-collateralise; relationships stay transactional rather than developmental. In many markets, this is compounded by weak credit bureaus, limited secured transactions infrastructure, and judicial bottlenecks. The consequence is a financing system that is rational at the micro level but suboptimal at the national level.

What works: building a financing ecosystem, not a single instrument

The most durable improvements come from shifting the underwriting logic. Digital payments, e-invoicing, tax e-filing, mobile money flows, and platform-based sales all generate alternative data that can reduce information asymmetry. But the strategic point is not “fintech disruption.” The goal is to convert economic activity into reliable, permissioned signals that lenders can use. Where that conversion happens, credit decisions become faster, cheaper, and more inclusive, often without lowering standards.

Supply-chain finance is a particularly pragmatic channel because it anchors SME credit to stronger counterparties and verifiable transactions. When SMEs sell to large buyers—public agencies, corporates, or exporters—the buyer’s payment obligation can be used to de-risk financing. That reduces reliance on fixed collateral and aligns credit with revenue generation. Yet it requires more than a product. It needs procurement discipline, invoice integrity, and digital workflows. Supply-chain finance succeeds when commercial and public systems cooperate on data and payment reliability.

Guarantee schemes can also play a role, but only under tight governance. Poorly designed guarantees can crowd out private discipline or become contingent liabilities that governments cannot manage. Well-designed guarantees, by contrast, can catalyse lending by absorbing a defined portion of risk, incentivising portfolio growth, and encouraging lenders to learn the segment. The difference lies in pricing, eligibility, claims management, and performance monitoring. A guarantee is not a subsidy; it is a risk-sharing contract that must be managed like one.

For growth-stage SMEs, equity and quasi-equity instruments matter as much as debt. Many SMEs are under-capitalised and attempt to finance expansion purely through working capital lines, which is structurally mismatched. Expanding access to venture-style capital is not realistic everywhere, but blended finance vehicles, local private equity, revenue-based financing, and structured funds can fill gaps where business models are viable but risk appetite is limited. The strategic discipline is to match instrument to business maturity, not to force all firms through the same debt funnel.

The policy and institutional agenda that unlocks scale

Finance reforms are often framed as technical upgrades, but the biggest gains come from institutional reliability. Secured transactions laws, collateral registries, movable asset frameworks, and faster enforcement can materially change lenders’ recovery expectations. Similarly, strengthening credit information systems and encouraging data interoperability across payments, tax, and registry platforms can reduce underwriting costs. SME finance scales when institutions reduce uncertainty, not when governments announce targets.

Public procurement also deserves attention as a financial lever. When governments pay suppliers late, they push liquidity stress down the supply chain, effectively forcing SMEs to finance the state. Timely, predictable payments can unlock supplier finance and reduce SME distress. In this sense, procurement reform is not only about governance; it is a balance-sheet intervention for the private sector. Where fiscal constraints exist, governments can still improve predictability through clearer payment calendars, verified invoicing, and transparent arrears management.

There is also a practical sequencing question. Formalisation is often presented as a prerequisite for finance, but it can be more effective as an outcome. When SMEs see tangible value—access to affordable credit, eligibility for procurement, or faster approvals—they have incentives to enter formal systems. The fastest route to formalisation is often to make it commercially useful.

The investment logic: focusing on bankability and delivery

For investors and DFIs, SME finance is attractive but difficult because performance depends on local execution. The most bankable strategies are those that control the underwriting pipeline, data quality, and collections capability, while operating under clear regulatory permissions. This is why partnerships between banks, fintechs, platforms, and public agencies are increasingly central: each holds a piece of the puzzle—balance sheet, distribution, data, or risk-sharing capacity. The key question is governance: who owns the customer, who owns the data, and who is accountable when things go wrong.

At a country level, expanding SME finance should be approached as an ecosystem programme with measurable operational outcomes—approval times, portfolio performance, cost-to-serve, and segmentation coverage—rather than a single product rollout. Without those metrics, it is easy to confuse disbursement volumes with impact, and credit growth with sustainable access. The objective is not to lend more; it is to lend better at scale.

Navigating these trade-offs requires more than generic “SME support.” It calls for integrated market intelligence, regulatory and institutional analysis, and delivery design that links finance instruments to the realities of informality, data scarcity, and enforcement constraints. At Aninver, we support clients in structuring SME finance initiatives that are both investable and implementable, drawing on experience across private-sector development, policy advisory, and programme design—including projects on SME competitiveness, inclusive growth strategies, and digital and institutional systems that strengthen market functioning. For more on how we approach private sector development and financing ecosystems, explore our Projects section or reach out for structured support in designing, de-risking, and delivering SME finance programmes.