Our Views

Off-Grid Solar for Rural Communities: How Mini-Grids Are Lighting Up Remote Villages

Off-grid energy is no longer a humanitarian afterthought. For governments under pressure to deliver services beyond capital cities, and for investors hunting for resilient infrastructure returns, rural electrification has become a test of state capability—planning, regulation, procurement, and long-term operations. Mini-grids are emerging as one of the few tools that can move faster than national grid extension while delivering something rural communities actually experience: reliable power, not occasional light.

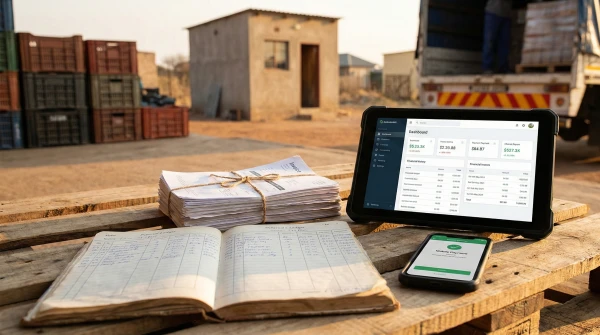

The technology story is broadly settled. Solar modules, batteries, inverters, and smart meters are cheaper and better understood than they were even a decade ago. What remains unresolved is the operating model: who takes demand risk, who sets tariffs, and who maintains assets for 10–15 years in places where roads, payments, and institutions are thin. Mini-grids “work” when they are treated as infrastructure with governance—rather than as kits deployed to meet annual targets.

Why mini-grids are winning the hard middle

In remote villages, the choice is rarely between the national grid and darkness. It is between three imperfect options: grid extension that may take years, solar home systems that meet basic household needs but struggle with enterprise loads, and mini-grids that can deliver higher-quality power locally. Mini-grids occupy the hard middle: they are more complex than household systems and faster than grid extension, which is precisely why they matter.

For policymakers, mini-grids can create credible near-term coverage without committing to uneconomic transmission lines. For investors, they offer the possibility—if structured correctly—of contracted cashflows from energy sales, with upside from productive demand growth. But the same features that make mini-grids attractive also create friction: they sit in the space where national utilities, rural agencies, local authorities, and private operators overlap. The biggest risk is not technical failure; it is institutional ambiguity.

The real constraint is demand, not watts

Mini-grid viability hinges on a single, uncomfortable fact: most rural communities start with low and variable demand. Households want lighting, phone charging, and perhaps a fan or television. That load alone rarely supports cost-reflective tariffs if the system is sized for reliability. The commercial puzzle is to anchor a predictable base load—mills, cold storage, telecom towers, water pumping, clinics—so that households can be served affordably without undermining the project’s economics. Bankability follows load certainty.

Demand estimation is where many programmes quietly fail. Too often, developers are forced to bid with limited data, then discover that the community’s ability to pay is seasonal, that appliance uptake is slower than expected, or that productive users prefer diesel for perceived reliability. Smart meters and remote monitoring help, but only if the programme is designed to learn and adjust—tariffs, service tiers, maintenance schedules—rather than pretending demand is static.

There is also a strategic trade-off in system design. Oversizing reduces outages and enables growth, but increases capital intensity and financial exposure. Undersizing keeps capex down, but can lock villages into low-power equilibrium and frustrate enterprises. The pragmatic approach is modularity: build for reliability today, with clear pathways to expand tomorrow, tied to verified uptake and enterprise development rather than optimistic forecasts.

Regulation can either unlock capital or freeze it

Mini-grids become investable when rules are predictable. Investors will tolerate rural risk; they will not tolerate regulatory improvisation. Tariff setting is central: a rigid, one-size national tariff may protect consumers in theory but can make rural systems financially impossible. Conversely, fully deregulated tariffs can create public backlash and political reversals. The workable middle is transparent tariff governance with targeted subsidy.

A second regulatory issue is the “grid arrival” problem. Developers fear that once a mini-grid is operating, the central grid could extend into the area and strand the asset. Communities fear being locked into higher tariffs than future grid electricity. Both are rational concerns, and both are solvable—if policy defines how integration happens. Compensation mechanisms, interconnection standards, and clear service territories turn a perceived threat into a managed transition. The question is not whether the grid arrives, but what happens when it does.

Licensing and permitting also matter more than they should. In many markets, the transaction costs of approvals can rival engineering complexity. Streamlined processes—standard documents, clear timelines, and delegated authority—reduce project delays and lower financing costs. If a programme requires hundreds of small projects, administrative friction becomes an economic variable.

Procurement must buy operations, not just hardware

Governments and donors often procure mini-grids like equipment: lowest cost, quick installation, ribbon-cutting. The infrastructure reality is different. A mini-grid is a service business with asset obligations—routine maintenance, component replacement, customer management, revenue collection, and outage response. If procurement does not price long-term operations, failures are pre-funded.

The most effective programmes shift from “build-and-hand-over” to performance-based approaches that reward uptime, customer connections, and service quality over time. Standardising technical specifications helps, but the deeper value comes from standardising contracts: service-level requirements, reporting obligations, escalation mechanisms, and remedies. This is where many governments need capacity: to draft documents that are enforceable, financeable, and fair to communities.

Local capacity is not a soft issue—it is a cost driver. Technicians must be trained, spare parts must be stocked, and operators must be present. When O&M is treated as an afterthought, downtime rises, collections fall, and communities revert to diesel or wood. Conversely, when operators build trust and reliable service, payment discipline improves—even where incomes are low—because electricity becomes a valued utility rather than a subsidy entitlement. Reliability is the strongest collection strategy.

Financing: the asset class is real, but the pipeline must mature

Mini-grids are capital-intensive upfront and cash-generative later, which makes them structurally financeable—but not always in rural currency and policy contexts. The typical obstacles are familiar: local currency depreciation against hard-currency debt, high cost of capital for early-stage developers, and thin balance sheets that cannot absorb construction risk across many sites. The financing gap is mostly about risk allocation.

Blended finance has a role, but it must be engineered with discipline. Concessional funding is most effective when it targets specific market failures—affordability gaps, early-stage development costs, or currency risk—rather than indiscriminately lowering tariffs. Results-based financing can sharpen incentives, but only if verification is credible and payment timelines match developers’ cash needs. Guarantees can unlock commercial debt, but only if the underlying contracts are bankable and disputes are manageable.

For private capital to scale, mini-grids must evolve from projects to portfolios. Aggregation reduces diligence costs, diversifies demand risk, and enables professional asset management. That requires standardised data—technical performance, collections, customer growth—and governance that can withstand investor scrutiny. What investors buy is not a village system; it is a repeatable model.

Making “light” translate into local growth

The strongest mini-grid programmes treat electrification as an economic development platform, not a social endpoint. Power enables value only when local economies can use it—through productive enterprises, improved services, and integration with markets. That means aligning mini-grids with agriculture, water, health, education, and SME policy, and removing bottlenecks that electricity alone cannot fix: refrigeration logistics, access to finance for appliances, business training, or market linkages.

Done well, mini-grids deliver a practical political dividend—visible service improvement—and a measurable economic one—new enterprises, higher productivity, and better public services. Done poorly, they create stranded assets and community distrust that can set the sector back years. The difference is execution: governance, demand, and operations.

For decision-makers, the priority is to treat mini-grids as an investable infrastructure market with clear rules, credible procurement, and data-driven oversight. Aninver supports governments, investors, and developers in building bankable pipelines—through feasibility and demand analysis, regulatory and procurement design, investment structuring, and programme governance. To explore relevant delivery experience, visit Aninver’s Projects section—or reach out for structured support in turning mini-grid ambition into operating reality.