Our Views

Public-Private Partnerships in Saudi Arabia: Trends, Frameworks, and Investment Opportunities

1.Introduction

Saudi Arabia is witnessing a paradigm shift in how it delivers infrastructure and public services, with Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) emerging as a central pillar of development under Vision 2030. The Kingdom’s ambitious reform agenda aims to diversify the economy and increase private-sector participation from 40% to 65% of GDP by 2030. PPPs have become a key mechanism to achieve these goals, enabling investment in vital projects across transportation, energy, water, waste management, education, healthcare, and housing. In fact, Saudi Arabia’s government has unveiled a PPP project pipeline of 200 projects in 17 sectors, one of the largest such pipelines globally. This burgeoning pipeline – spanning mega-infrastructure and social services – reflects the country’s commitment to engaging private capital and expertise to drive national development. As a result, “Saudi Arabia PPP projects” have become a focal point for regional investors, making the Kingdom one of the most attractive destinations for PPP investment in the Middle East.

In this article, we provide an in-depth overview of the current landscape of PPPs in Saudi Arabia. We examine active sectors and recent deals in both hard infrastructure (transportation, energy, water, waste) and social infrastructure (education, healthcare, housing). We also analyze the institutional framework – including the role of the National Center for Privatization & PPP (NCP) – and recent legal and policy developments that underpin the program. Key project examples and data from InfraPPP World (Aninver’s infrastructure market intelligence platform) and other authoritative sources are highlighted to illustrate trends and opportunities. We then discuss financing patterns, private sector participation, and challenges in project structuring. Finally, we contextualize Saudi Arabia’s PPP program within Vision 2030’s objectives and the broader Gulf PPP projects ecosystem, showing how the Kingdom is leading the way in the Middle East PPP projects market.

2. The Current PPP Landscape in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s PPP landscape has expanded rapidly, transforming PPPs from a niche procurement alternative into a mainstream development model. Today, the Kingdom accounts for a large share of PPP activity in the Gulf region. No longer limited to the oil and power sectors, Saudi Arabia’s PPP program now spans a diverse array of projects. According to market estimates, Saudi Arabia comprises the vast majority of the GCC’s social infrastructure PPP pipeline. This boom is not driven by fiscal necessity alone – with high oil revenues, Saudi Arabia’s budget deficit is modest (projected ~1.9% of GDP) – but by the pursuit of efficiency, innovation, and economic diversification. In other words, PPPs are chosen for their value-for-money and service quality benefits rather than just as a funding of last resort.

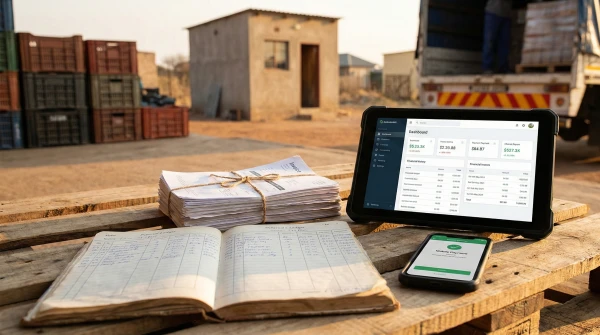

Fig 1 . InfraPPP, one of the leading PPP market intelligence platforms has been a key source of information for this article

A few indicators highlight the scale and momentum of Saudi Arabia’s PPP program:

- Massive Project Pipeline: In 2023, the NCP launched a Privatization & PPP pipeline of 200 approved projects across 17 sectors, inviting local and international investors to prepare for upcoming tenders. This pipeline – the largest in the region – underscores the government’s commitment to transparency and deal flow, and is directly aligned with Vision 2030 goals of increasing private investment and improving services. NCP officials note that information on 140+ projects is already available to investors, with more to come.

- Multisector Coverage: Saudi PPP projects now span infrastructure and social sectors. Traditional infrastructure like transport, energy, and water continue to see PPP investment, but there’s also significant growth in social infrastructure PPPs such as hospitals, schools, and housing. This broad sectoral mix is evident in the NCP’s pipeline and recent deals. For example, the project pipeline includes major transportation projects, utilities, municipal services, and even sports facilities, reflecting the drive to privatize or partner out services in 16+ sectors.

- High Investor Interest: PPP opportunities in Saudi Arabia are attracting strong interest from both domestic and international players. In April 2023, the Ministry of Health (MOH) and NCP launched an Expression of Interest (EOI) for three long-term care hospital projects – and received over 420 applications from companies across 19 countries. This overwhelming response illustrates global investor confidence in Saudi PPP projects. Likewise, when the MOH tendered a diagnostic radiology services PPP earlier in 2023, it drew bids from leading healthcare consortia and was successfully awarded to a private alliance. In education, the first bundle of 60 schools under a schools PPP program saw 87 expressions of interest and multiple consortia bids. These examples show that Saudi Arabia’s PPP program is on the radar of major international developers, operators, and financiers.

- Major Deals Across Sectors: Recent PPP deals underline the variety and scale of projects coming to fruition. In the water sector, Saudi authorities have closed several large desalination and sewage projects with foreign-local consortiums – for instance, the Jubail-3A independent desalination plant (capacity 600,000 m³/day) was inaugurated in mid-2023 at a cost of US$650 million. In transport, a consortium led by Italy’s Webuild signed a €1.4 billion (US$1.5 billion) contract to design and build 57 km of high-speed railway along the Red Sea coast in NEOM city– part of an innovative PPP for the futuristic megacity’s transport network. Meanwhile, in housing, Saudi conglomerate Nesma Holding announced a SAR 3.45 billion (US$919 million) investment to develop residential communities in NEOMunder a PPP-style structure, expanding housing infrastructure for the planned smart city. These deals illustrate the breadth of sectors – from water and rail to new city development – being unlocked via PPPs in Saudi Arabia.

In summary, the current landscape of PPPs in Saudi Arabia is robust and growing, fueled by political will, Vision 2030 targets, and a well-stocked pipeline of projects. The Kingdom has firmly positioned itself as a regional leader in PPPs, with both the “Vision 2030 infrastructure” agenda and investor appetite driving continued momentum.

3. Institutional Framework and PPP Policy in Saudi Arabia

A strong institutional and regulatory framework underpins Saudi Arabia’s PPP program, providing clarity and confidence to investors. The central orchestrator is the National Center for Privatization & PPP (NCP), established in 2017 to oversee the privatization agenda and facilitate PPP projects. NCP works closely with line ministries and government entities to identify suitable projects, standardize processes, and ensure projects align with national objectives. It also acts as a gatekeeper for applying the PPP law and regulations across sectors. As Vision 2030’s dedicated Privatization Program manager, NCP’s mandate is to increase private-sector involvement in public services, improve infrastructure, and attract investment. High-level support for NCP comes from the Council of Economic and Development Affairs (CEDA), chaired by the Crown Prince, which provides policy direction and can swiftly intervene to resolve bottlenecks (e.g. expediting permitting for PPP projects).

A milestone in Saudi Arabia’s PPP framework was the passage of the Private Sector Participation (PSP) Law in 2021, the country’s first comprehensive PPP law. Before 2021, PPPs were conducted under general procurement law or sector-specific frameworks. The PSP Law (sometimes called the Privatization Law) now provides a formal legal foundation for PPPs, covering all contractual partnerships between public and private sectors. Crucially, it codifies the PPP procurement process and standardizes how projects are tendered and managed, which greatly improves transparency and predictability for bidders. Under the law, government authorities must prepare detailed pre-bid documentation (feasibility studies, draft contracts, risk allocation, etc.) and follow a clear sequence of steps – project identification, approval, request for qualification, RFP issuance, bid evaluation, etc. – overseen by NCP. This level of prescription gives private investors certainty and consistency, reducing risk in bidding for Saudi PPP projects.

The PSP Law and its implementing regulations also introduced investor-friendly provisions that address historical concerns. Notably, the law permits arbitration for dispute resolution, including arbitration outside Saudi Arabia if agreed, which is a major assurance for international lenders and sponsors. It mandates equal treatment of foreign and local investors in PPP procurements, ensuring a level playing field for global companies. The law even allows NCP to exempt certain projects from “Saudization” labor quota rules, recognizing that highly specialized projects may need flexibility in staffing. Additionally, PPP contracts can include government payment guarantees or termination compensation clauses, and private partners may be allowed to collect revenues directly from users in some projects (a practice previously restricted). Together, these features make Saudi Arabia’s PPP framework one of the more robust and comprehensive in the GCC, comparable to recent PPP laws in the UAE, Oman, and Kuwait.

Alongside NCP and the legal framework, Saudi Arabia has built sector-specific institutions to drive PPP projects:

- In the water sector, the Saudi Water Partnership Company (SWPC) is the dedicated procuring authority for water and wastewater PPPs. SWPC plans and tenders projects like independent water plants (IWPs), sewage treatment plants (ISTPs), and water reservoirs. It has a rolling pipeline of projects to meet Vision 2030 water goals, and has introduced pre-qualification programs to streamline bidding and encourage robust competition. The Water Transmission and Technologies Co. (WTTCO) handles upcoming water transmission pipeline concessions, with an enormous pipeline of 485 projects (over 10,000 km of pipes) planned up to 2030. The National Water Company (NWC), which operates existing urban water networks, is also engaging the private sector via long-term management contracts for city water systems and by participating in new wastewater PPPs as a government off-taker.

- In transportation, sector bodies like the Ministry of Transport and logistic agencies have worked with NCP to identify PPP opportunities. For example, the Saudi Railway Company and civil aviation authority have explored PPPs for new rail lines and airport expansions (the Madinah Airport was an early PPP success story). Recently, the Al-Madinah Region Development Authority pre-qualified bidders for a bus rapid transit (BRT) network PPP in Medina, and the transport ministry is preparing tenders for highway service center PPPs on major inter-city roads. For airports, the government is moving toward privatization/PPP of various airports to improve service and expand capacity, building on lessons from the Medina Airport concession and earlier privatization of airport management.

Fig 2. Madinah Airport PPP is one the most important PPP projects in airports in SA

- In education, the Tatweer Building Company (TBC), a government-owned entity, acts as the implementation arm for school infrastructure PPPs. TBC bundled and tendered the first “waves” of the Schools PPP Program, which involve private consortia designing, building, and facilities-managing groups of public schools on a long-term concession. TBC and the Ministry of Education closed Wave 1 (60 schools in Jeddah and Makkah) in 2020 and have launched Wave 2 (60 schools in Medina), with plans for many more waves to ultimately reach thousands of schools under PPP by 2030.

- In healthcare, the Ministry of Health has set up a PPP unit and is collaborating with NCP on various initiatives – from new hospital projects to outsourcing of clinical services. For complex projects, external advisors including the International Finance Corporation (IFC) have been engaged to structure PPP deals (e.g. the Al-Ansar Hospital PPP in Madinah). The MOH is also undergoing a wider transformation to create regional health clusters and corporatize public hospitals, which will pave the way for more PPP and private management opportunities.

This institutional ecosystem – strong central oversight by NCP combined with empowered sectoral PPP units – has built the capacities needed for a successful PPP program. The government’s policy commitment is evident: PPPs and privatization are explicitly identified as a means to achieve Vision 2030 objectives of improved quality of life and enhanced government services. Publishing the project pipeline and courting investors through global roadshows (NCP’s 2023 marketing campaign) further signal that Saudi Arabia is “open for business” in PPP. As a result, the Kingdom’s PPP program rests on solid institutional ground, with clear frameworks to guide the huge pipeline of projects from concept to contract.

4. Infrastructure PPP Projects: Transport, Energy, Water and Waste

Saudi Arabia’s PPP drive initially gained traction in infrastructure sectors, where the need for capital-intensive development is high. Today, PPP projects in transport, energy, water and waste are proliferating, supported by sector-specific plans and successful precedent transactions. Below we explore trends and examples in these key sectors:

Fig 3. InfraPPP publishes quarterly together with the World Association of PPP Practitioners the QUARTERLY PPP DEAL UPDATE

4.1. Transport Sector PPPs

In the transport sector, Saudi Arabia is leveraging PPPs to develop highways, railways, ports, and airports. An early landmark was the Prince Mohammed bin Abdulaziz International Airport in Madinah, which became the Middle East’s first airport project procured as a PPP. The airport’s expansion and operation were concessioned to a private consortium in 2012, and its on-time completion and successful operation have often been cited as a model. This success helped build confidence for private investment in Saudi transport projects.

More recently, attention has turned to surface transport. Saudi Arabia’s ambitious plans for inter-city rail and urban transit are creating PPP opportunities. In the $500+ billion NEOM smart city project on the Red Sea coast, a high-speed railway is under development via PPP, forming part of the city’s integrated transport system. In May 2023, a consortium led by Webuild (Italy) and Shibh Al Jazira (Saudi) signed a EUR 1.4 billion contract to design and build 57 km of NEOM’s high-speed railway. This project, which will connect key regions of NEOM, is being delivered under a PPP-like structure (Design-Build-Finance) supported by the Public Investment Fund (PIF). It exemplifies how “PPP investment Saudi Arabia” is facilitating mega-projects that blend public vision with private sector execution.

On the roads side, the government is introducing PPP models to develop and operate select highway facilities. The Ministry of Transport, in coordination with NCP, announced plans to tender service area concessions on major highways – for instance, service/rest stop PPPs on the Jeddah–Makkah highway and the Jeddah–Jazan highway. Under these projects, a private partner will finance and upgrade service stations and possibly manage tolling or commercial activities for a concession term, improving amenities for travelers at no upfront cost to the government. These would be among the first highway PPPs in the Kingdom. Likewise, urban transport is opening up: the Medina BRT project mentioned earlier plans to involve a private operator to develop and run a new bus rapid transit network, expanding public transit with private capital and expertise.

Port infrastructure is another area seeing PPP involvement. Saudi Arabia has several major port privatization initiatives (some structured as concessions). In 2022, the Zakat, Tax and Customs Authority (ZATCA) – which oversees customs facilities at ports and borders – announced a pipeline of seven PPP projects, largely focused on ports and related logistics infrastructure. These include projects to upgrade port facilities, renewable energy installations at port sites, and even an unusual PPP to develop and manage a canine training center for customs inspections (a PPP to build and operate kennels and train sniffer dogs). While the latter is niche, it underscores that no project is too small or unusual for the PPP model if it delivers value. Major seaports like Jeddah and Dammam have already involved private terminal operators for years, and full privatization of port operations is underway as part of the wider privatization program.

Lastly, airports continue to feature in Saudi Arabia’s privatization pipeline. Following the Madinah Airport PPP, Saudi Arabia has sought to involve the private sector in other airports through management contracts or sale of stakes (e.g. a stake in Riyadh Airport was sold to a foreign investor). In 2023, the government announced the opening of the new Red Sea International Airport, part of the Red Sea tourism project, which was developed with private sector design and will likely have private operators. As more airports are modernized, we can expect PPP or lease models to be used for terminals, cargo facilities, and airport city developments to harness private financing.

Overall, transport PPPs in Saudi Arabia are moving beyond the power and operate model to include greenfield development of new networks, with the state acting as enabler and regulator. Backed by Vision 2030’s focus on infrastructure (from new rail lines to logistics hubs), Saudi Arabia’s transport pipeline offers significant opportunities for investors with long-term horizons in the region’s largest economy.

4.2. Energy Sector PPPs (Power and Renewable Energy)

Saudi Arabia’s energy sector has been at the forefront of PPP utilization for decades, primarily through the Independent Power Producer (IPP) model. Even before the formal PSP law, Saudi Arabia routinely partnered with private developers to build power generation capacity – especially in utilities like electricity generation and desalination – under long-term offtake contracts. The country’s Vision 2030 includes bold energy targets, such as generating 50% of power from renewable sources by 2030, and PPPs are crucial to achieving these goals.

In the power generation subsector, Saudi Arabia’s Renewable Energy Project Development Office (REPDO) has run a transparent, multi-round competitive IPP program for solar and wind projects. Since 2017, three bidding rounds have been launched, resulting in 12 solar IPP projects totaling 3.3 GW of capacity awarded to consortia of private developers. These projects, spread across the Kingdom, have attracted leading international renewable companies and investors (e.g. EDF, Masdar, ACWA Power) and achieved some record-low solar tariffs. The success of this program is attributed to bankable project structures and standardized contracts, as well as Saudi Arabia’s strong credit support (through the state offtaker). A fourth round including more solar and the first large wind farms is in the pipeline. The Kingdom is also executing larger flagship renewable projects via PIF-led joint ventures – for example, the 1.5 GW Sudair Solar PV project (one of the largest solar plants in the world) is being developed with private partners under a PPP framework, and a 400 MW Dumat Al Jandal wind farm has already come online via a PPP with EDF and Masdar.

For conventional power, Saudi Arabia likewise uses PPPs for independent power plants (combined-cycle gas plants, etc.), though the pace has slowed as the focus shifts to green energy. Nonetheless, existing IPP projects like the Riyadh PP11 gas plant and others are examples of successful financing of thermal plants by private consortia with long-term power purchase agreements from the Saudi Electricity Company.

Perhaps the most cutting-edge energy PPP in Saudi Arabia is the NEOM Green Hydrogen project – a US$5 billion venture to produce green hydrogen and ammonia, which is structured as a PPP between NEOM (via PIF), ACWA Power, and Air Products. While not a traditional public service PPP, it exemplifies the innovative large-scale projects being pursued by blending public vision and private sector technology/capital. It reached financial close in 2023 and is under construction, highlighting Saudi Arabia’s willingness to use partnership models for pioneering projects.

4.3. Water and Waste Sector PPPs

The water sector in Saudi Arabia is one of the most active areas for PPPs, supported by a pressing need for water infrastructure and a mature regulatory environment. Saudi Arabia has long been the world’s largest producer of desalinated water, and historically many desalination plants were government-built. But in recent years, virtually all new large desalination facilities and wastewater treatment plants are developed as PPPs (specifically BOOT – Build-Own-Operate-Transfer – projects). This approach aligns with Vision 2030 goals for sustainable water management and private sector participation.

As of 2025, Saudi Arabia’s government has announced over 40 water PPP projects, including seawater desalination plants, sewage treatment plants, and even strategic water storage facilities. Examples include the Madinah-3, Buraydah-2, and Tabuk-2 ISTP projects, three sewage treatment plants awarded in 2020 to a consortium of Spain’s Acciona Agua and Saudi partners (Tamasuk and Tawzea). These projects, with a combined value exceeding $700 million, achieved financial close in 2022 – even amidst the pandemic – showing investor confidence in the Saudi water PPP model. Under 25-30 year concessions, the private consortia will finance, build, and operate the plants, with the government guaranteeing offtake of the treated water. Similarly, on the desalination side, projects like Rabigh-3, Shuaibah-3 Expansion, Jubail-3A and 3B, Al Khafji, Yanbu-4, and others have been tendered to private developers (often partnerships between Saudi infrastructure firms and global water companies). These independent water producer (IWP) projects have added millions of cubic meters per day of capacity. For instance, the Jubail-3A desal plant mentioned earlier (inaugurated by ACWA Power) produces 600,000 m³/day of potable water. Its sister project Jubail-3B, a 570,000 m³/day plant, was awarded to a consortium led by France’s EDF and UAE’s Masdar in 2021, with solar PV integration to reduce energy costs. According to recent reports, Saudi Arabia continues to expand its water PPP pipeline, with eight new projects valued at $8 billion announced in late 2024 to be awarded over the next 12 months. These include more ISTPs (such as new wastewater plants in Makkah) and additional large IWPs, indicating an ongoing, rolling program of water PPP procurements by SWPC.

Crucially, the water PPP program benefits from clear sector planning and regulation. The National Water Strategy 2030 provides the roadmap for sustainable water development, and the 2020 Water Law modernized sector governance. SWPC, as noted, is the lynchpin – it ensures that each project is structured attractively for bidders, often with government support in land and offtake. The typical financing structure for these water PPPs is project finance: consortia secure long-term loans from a mix of local Saudi banks and international lenders, backed by the security of government-payment underpinning (usually via capacity charges or water purchase agreements). An example of financing innovation is green loans for desalination – in 2020 the Shuaibah-3 IWPP refinancing was certified as the first green loan in Saudi Arabia, reflecting the improved efficiency and sustainability of new desal technology.

In the waste management sector, PPPs are in earlier stages but gathering pace, especially for waste-to-energy (WtE) and recycling facilities. The Saudi Investment Recycling Company (SIRC, a PIF subsidiary) has outlined plans to develop multiple waste treatment and WtE plants through PPP models to meet national recycling targets. In March 2022, SIRC and the National Center for Waste Management launched a tender for an integrated waste management PPP in Riyadh, aiming to partner with a private firm to design, build, and operate advanced waste treatment facilities for the capital city. This project is expected to include recycling and possibly energy recovery components, reducing landfill usage. Several international waste management firms expressed interest. Additionally, other municipalities are considering PPPs for landfill rehabilitation and waste collection services modernization. While no major WtE plant has reached financial close yet in KSA, the pipeline is promising – Saudi Arabia’s large waste volumes and government support make it a prime candidate for successful PPP-driven WtE projects in the near future.

In summary, infrastructure PPPs in Saudi Arabia span a wide spectrum – from building new roads and railways, to expanding power generation through IPPs, to ensuring water security via desalination plants, to modernizing waste management. These projects have attracted top-tier private partners and billions in investment. For investors and contractors, the appeal lies in Saudi Arabia’s stable long-term demand, creditworthy government counterparties, and a now well-established PPP framework that offers transparency and risk mitigation. For the Saudi government, leveraging PPPs in infrastructure brings efficiency gains and allows access to global technology and know-how – aligning with the Vision 2030 aim of world-class infrastructure without overburdening public finances.

4.4. Social Infrastructure PPPs: Education, Healthcare, and Housing

Beyond traditional infrastructure, Saudi Arabia is also pioneering PPPs in social sectors – notably education, healthcare, and housing – which were historically delivered almost entirely by the government. Incorporating private sector innovation in these areas is seen as vital to improve service quality and meet growing citizen needs. As a result, a robust pipeline of social infrastructure PPP projects has emerged, making Saudi Arabia a regional leader in this segment of PPP as well.

Education PPP Projects

The Education PPP program in Saudi Arabia centers on addressing school infrastructure needs. With over 38,000 schools nationwide (80% public), the government launched a PPP initiative to build and maintain public school buildings through private consortia, allowing the Ministry of Education to focus on curriculum and teaching. Under this program, schools are bundled into “waves” of ~60 schools. In Wave 1, a contract to finance, design, build, and facilities-manage 60 public schools in Jeddah and Makkah was awarded in 2019 and achieved financial close by late 2020. This project brought in private financing and international expertise for modern school design, with the private partner responsible for maintaining the facilities for 20+ years in return for availability payments from the government.

Following that success, Wave 2 (another 60 schools in Medina) was tendered, and as of 2023 a preferred bidder had been announced. Notably, the Kingdom’s ambition doesn’t stop at a few dozen schools – it plans to procure up to 4,000 schools via PPP by 2030. This staggering number indicates the scale of opportunity for investors in the education space. By partnering with private developers, Saudi Arabia aims to rapidly build new schools (or replace aging ones) to accommodate a young and growing population, while ensuring these facilities are kept at high standards through professional facility management. Global infrastructure investors and local contractors have shown strong interest in these school bundles, as the projects offer stable, government-backed revenue over a long term. The “hard” aspect (construction) is straightforward, and the “soft” aspect (maintenance services) can be optimized by specialized firms – creating a win-win that improves learning environments for students. Indeed, performance-based PPP contracts for schools can lead to better-maintained classrooms, reliable utilities, and cleaner campuses than might be achieved under traditional public procurement.

Fig 4 . Social PPPs are taking increasing relevamce in SA (Education, Helathcare, Housing)

Healthcare PPP Projects

In the healthcare sector, Saudi Arabia’s PPP approach is multifaceted, covering both healthcare facilities and services. The Ministry of Health’s privatization strategy calls for increasing the private sector’s share in healthcare provision from 25% to 30% in the near term, and PPPs are a key tool to reach that target. One track has been outsourcing specialized medical services via PPP. For example, the MOH recently awarded a Diagnostic Imaging Services PPP – a contract under which a private consortium (led by Altakassusi and Alliance Medical) will provide radiology services (MRIs, CT scans, etc.) across selected public hospitals. The private partner will invest in imaging equipment and operate the service to agreed performance standards, being paid based on outcomes and volumes. This model injects private efficiency into clinical services and ensures up-to-date technology for patients. It is expected to deliver better results for over one million beneficiaries across seven hospitals.

Another track is building new healthcare facilities via PPP. A flagship project is the Al-Ansar Hospital PPP in Madinah, a 244-bed new hospital near the Prophet’s Mosque. Tendered in 2022, it attracted 87 EOIs and proceeded with 9 qualified bidders, illustrating the strong market interest. The winning consortium will finance and construct the hospital and may also provide non-clinical services, while the government (or health insurance system) covers clinical operations. Similarly, the MOH has issued EOIs for long-term care hospitals and rehabilitation centers via PPP, as mentioned earlier – receiving hundreds of investor applications globally. By engaging private operators for such facilities, Saudi Arabia hopes to expand healthcare capacity (e.g. more hospital beds) without solely relying on public capital, and to tap into the expertise of specialized healthcare operators.

The health sector PPP push is reinforced by broader reforms. The MOH is transitioning to an integrated care model with regional health “clusters” and corporatizing hospitals, which will allow private operators to manage public hospitals or clinics in the future. We have already seen the first hints of this in the form of partnerships for dialysis services and primary care center upgrades. In addition, medical cities and research hospitals could be areas for joint ventures or PPPs. The public policy trend in Saudi healthcare is clear: move from a state-provider model to a mixed system where the government regulates and funds, but a significant portion of actual service delivery is handled by private entities (for-profit or non-profit). This will manifest in more PPP contracts for areas like imaging, labs, oncology centers, and possibly facility management of entire hospitals.

Housing and Social Infrastructure PPPs

Housing is another social domain where PPPs and privatization intersect with Saudi objectives. The housing challenge in Saudi Arabia includes providing affordable homes for citizens and accommodating the workforce needed for the Kingdom’s mega-projects (like NEOM and the Red Sea project). While housing development is largely driven by the private real estate market, there have been instances of partnership models. For example, as noted above, Nesma’s US$919 million investment in NEOM’s residential communities can be seen as a PPP-like venture, where a private firm is developing housing (including potentially worker housing or affordable units) in collaboration with the public developers of NEOM. On a more traditional note, the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs and Housing has explored PPP structures for affordable housing projects and redevelopment of government land, essentially inviting private developers to build housing on government land with profit-sharing arrangements or long-term leases.

Additionally, social care facilities are being tendered via PPP. In mid-2022, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development (MHRSD) launched a request for EOI for Social Care Homes PPPs in Riyadh and Jeddah. These projects aim to engage private operators to build and run care homes for the elderly or disabled, ensuring better quality of care. The private sector’s role would include facility provision, maintenance, and possibly certain hospitality services, while the government would fund the care and oversee standards. This is a novel application of PPP in the social welfare sphere, showing the government’s willingness to extend the model beyond revenue-generating infrastructure into service-oriented facilities.

Finally, sports and recreation have even entered the PPP conversation. Saudi Arabia stunned the sports world in 2023 by announcing the privatization of major football clubs and facilities – a move to catalyze investment in sports under Vision 2030’s Quality of Life program. While not PPP in the traditional sense (it’s more privatization), it complements PPP efforts by inviting private investment in sports infrastructure. For instance, new stadiums or sports academies could be developed through PPPs. The Crown Prince’s initiative to privatize sports clubs aims to generate private investment and boost the sports economy from a few hundred million to over SAR 1.8 billion annually. This underscores that public-private partnership in Saudi Arabia is not just about hard infrastructure but also about leveraging private capital for wider socio-economic goals – from healthier lifestyles to tourism.

In conclusion, Saudi Arabia’s expansion of PPPs into social infrastructure sectors like schools, hospitals, and housing is a significant trend setting it apart from many peers. The government is effectively saying: if a public service can be delivered better or faster with private involvement, we are open to that. This creates a host of opportunities for investors in education and healthcare real estate, facilities management companies, and service providers across the board. It also poses new challenges – these sectors require careful outcome-based contracts and oversight to ensure citizens receive high-quality services and that equity (affordability, access) is maintained. Thus far, the trajectory is positive, with early projects in education and health achieving strong response and moving forward. Saudi Arabia is gradually building a track record in social PPPs that will give confidence for bigger projects in the future, potentially including entire university campuses, hospitals, or housing communities developed through PPP frameworks.

5. PPP Financing, Investment Trends and Challenges

With the vast scope of Saudi Arabia’s PPP program, financing trends and investor participation are critical components to examine. The good news is that Saudi PPP projects have generally found no shortage of willing financiers or partners, thanks to the country’s strong credit, sizable deals, and the reforms making the regulatory environment more predictable. However, expanding PPP into new sectors and the sheer volume of projects does present challenges that the Kingdom is working to address.

Financing Trends: Saudi Arabia’s PPP projects are typically financed through a combination of equity from project sponsors and non-recourse project finance debt from banks. The Kingdom benefits from a deep pool of local banks (and Islamic finance institutions) with large balance sheets and appetite for infrastructure deals, as well as ready access to international project finance banks. Many deals have seen oversubscription by lenders, and competitive tension has driven financing costs down. For example, recent water PPPs achieved very attractive interest rates and tenors, reflecting confidence in SWPC’s offtake agreements. In power and water projects, it’s common to see local banks like National Commercial Bank or Riyad Bank lending alongside international banks like Standard Chartered or MUFG. The financing of Abu Dhabi’s Noor-2 street lighting PPP – while in the UAE – is illustrative: a 50:50 debt-equity structure with Standard Chartered underwriting and later syndicating debt, and even providing an equity bridge loan to the sponsor. Saudi PPPs see similar structures. The introduction of green and sustainability-linked financing is also on the horizon as Vision 2030 emphasizes ESG goals (e.g. desalination plants powered by renewables may seek green loan certification).

A significant development was the creation of the National Infrastructure Fund (NIF) in 2021. Backed by the Saudi sovereign wealth entities and advised by BlackRock, the NIF is set to deploy up to SAR 200 billion (US$53 billion) into infrastructure projects over the next decade. It will invest in sectors like water, transportation, energy, and health, effectively co-financing or providing credit support to PPP projects. The NIF began operations in 2022 and is expected to catalyze projects that might face financing gaps or need longer tenors than commercial banks typically offer. This is an important tool to ensure the huge PPP pipeline can be funded on favorable terms, and to crowd-in private finance by de-risking some elements (for instance, NIF might offer subordinated debt or guarantees).

Private Sector Participation: Saudi Arabia’s PPP program has attracted a who’s who of global infrastructure players. On the development side, companies such as ACWA Power (a homegrown Saudi firm now a global leader in PPP projects), ENGIE, EDF, Sumitomo, ACCIONA, Veolia, Marubeni, TAV Airports, Webuild, and many others have participated in bids and formed consortia with local partners. Foreign investors are often required or incentivized to team up with Saudi companies, which aligns with localization goals and knowledge transfer. The PSP Law’s assurance of equal treatment for foreign and local bidders has made the market even more appealing to international firms. Notably, Saudi conglomerates and contractors – Nesma, Saudi Binladin Group, Aljomaih, Abdul Latif Jameel, El-Seif, etc. – are frequently part of PPP consortia, providing local expertise, O&M capabilities, or equity. This melding of international and local strengths has been a hallmark of Saudi PPP deals, as seen in the Acciona-led consortium for multiple ISTPs which included two Saudi partners.

Investor interest is further buoyed by the sheer scale of opportunities (few markets offer the prospect of 200+ PPP projects in a pipeline). As evidence, when Saudi Arabia opened prequalification for upcoming water projects in late 2024, dozens of firms applied for each project . The competitive tension benefits Saudi Arabia by achieving better commercial terms and technology inputs. However, it also challenges the government to efficiently manage procurement timelines and bidder expenses – something NCP is cognizant of, hence efforts to streamline pre-bid processes.

Challenges in Project Structuring and Procurement: Despite the generally positive trajectory, Saudi Arabia’s PPP program faces several challenges:

- Capacity and Execution Speed: Launching hundreds of projects is a double-edged sword. While the pipeline is impressive, ensuring that public-sector teams can prepare, tender, and manage all these projects in a timely manner is challenging. Some projects have seen delays in tendering or award, often due to the rigorous approval process (projects must clear feasibility and get CEDA and Ministry of Finance approvals). Building capacity within ministries and NCP to handle simultaneous procurements is ongoing. To address this, Saudi Arabia has invested in PPP capacity building and often hires experienced transaction advisors (financial, legal, technical consultants) to support government teams on each project. This mitigates delays and helps structure bankable deals.

- Risk Allocation: Getting the risk allocation right in contracts is vital for bankability. The new PSP Law has helped standardize this, but in practice there can be negotiation on points like demand risk, land availability, foreign exchange, or termination payments. For instance, if a project involves user-paid fees (say a toll road or an airport), investors will want traffic risk mitigants or revenue guarantees initially. The government generally prefers an availability payment model for social projects to avoid user fee risk for investors – as used in the schools PPPs – which is well-received by financiers. Nonetheless, some sectors are untested (e.g. a toll highway PPP in Saudi Arabia has not been done yet), so both parties will need to carefully distribute risks to ensure bids are forthcoming and financing is smooth.

- Regulatory and Contract Enforcement: Implementing a brand-new PPP law across various agencies is a learning process. Ensuring that all stakeholders (from ministerial tender committees to local banks and contractors) understand the PPP contractual frameworks is essential. There may be a need for refining dispute resolution mechanisms as projects progress into operations. However, the inclusion of international arbitration in contracts is a strong reassurance. So far, Saudi PPPs have not encountered major disputes publicly, but as the portfolio grows, robust governance of contracts will be tested.

- Economic and Financial Factors: While Saudi Arabia’s currency (riyal) is stable and pegged to the USD, macroeconomic shifts like interest rate rises can impact PPP financing costs. The global increase in interest rates in 2022–2023, for example, means new PPP projects could be more expensive to finance than those closed in the low-rate environment of 2018–2019. The government might need to adjust evaluation models or provide support (like interest rate hedging mechanisms) if needed to keep projects viable. Inflation in construction costs is another challenge; with so many projects concurrently, there is risk of contractor capacity constraints or price escalation in materials. Early projects have benefited from competitive EPC pricing, but maintaining that will require careful pipeline scheduling and perhaps attracting international contractors to augment local ones.

Despite these challenges, Saudi Arabia has shown flexibility and a problem-solving approach. A pertinent example is the Madinah Airport PPP: when airline traffic dipped due to external factors, the government and the private operator worked on a financial restructuring to rebalance the concession, rather than let the partnership fail. This kind of pragmatism boosts long-run investor confidence – they see that the government is committed to partnership in spirit, not just in name, and will adapt to ensure mutual success. As more projects reach operation, continuous learning and refinement of the PPP framework are expected, further reducing challenges for future deals.

6. PPPs in Vision 2030 and the Broader Middle East Context

Saudi Arabia’s PPP program is a cornerstone of Vision 2030, and its success has implications not only for the Kingdom but for the wider Middle East. Under Vision 2030, the Privatization Program (which encompasses PPPs) is tasked with unlocking value in state assets, increasing non-oil revenues, and improving services through private sector efficiency. Key targets include generating SAR 60 billion in non-oil revenue by 2025 and creating thousands of jobs via privatization. PPPs contribute directly to these targets by attracting investment (both foreign and domestic) and by fostering industries (construction, facilities management, etc.) that create employment.

Fig 5 . Saudi Arabia’s PPP program is a cornerstone of Vision 2030

The linkage between PPPs and Vision 2030 can be seen in almost every major initiative:

- The massive infrastructure developments (airports, metros, digital cities) enable the economic diversification and quality of life improvements Vision 2030 envisions.

- The social PPPs in health and education directly contribute to improving human capital and social services, which is a pillar of the Vision.

- Even sectors like tourism (where Saudi is developing new destinations) will likely use PPP models for visitor facilities, aligning with Vision 2030’s goal of expanding tourism’s GDP share.

Saudi policymakers view PPPs as a way to accelerate projects that would otherwise strain public budgets. By doing so, they avoid delays in infrastructure that could impede growth. At the same time, PPPs shift some of the long-term operational burden to the private sector, which often leads to innovation – e.g., energy-efficient school designs or advanced hospital management systems introduced by private partners. This resonates with the Vision’s theme of a vibrant society empowered by world-class infrastructure.

In the Gulf and Middle East region, Saudi Arabia’s PPP drive has a demonstrative effect. Historically, countries like the UAE and Kuwait have used PPPs selectively (Kuwait had a slow PPP program; the UAE did mostly government-funded projects until recently). But now many GCC states have passed new PPP laws (Dubai in 2015, Oman in 2019, Qatar in 2020, Kuwait updated its framework, etc.). Saudi Arabia’s large-scale implementation under Vision 2030 sets a benchmark and provides learnings for its neighbors. It’s telling that Saudi Arabia, despite being the largest Gulf economy with ample oil revenues, is championing PPPs – underlining that PPPs are not just for countries with budget issues, but for those seeking efficiency and innovation. As one analysis noted, what drives Gulf PPP development now is “more about net present value benefit and not government balance sheet relief”, a mindset clearly reflected in Saudi Arabia.

Regionally, we see a bit of healthy competition and collaboration. For example:

- Saudi Arabia’s social infrastructure PPP push (schools, healthcare) is being closely watched by the UAE, which has started its own schools PPP pilot and is considering hospital PPPs. A recent report highlighted that Saudi Arabia accounts for as much as 75% of the GCC’s social infrastructure PPP pipeline, indicating Saudi’s lead.

- In utilities, Saudi’s model has been emulated – Oman’s water authority and UAE’s ADWEA have hired some of the same advisors and adopted similar contractual structures as SWPC for their water PPPs. This creates a more integrated GCC PPP market, where investors see opportunities across borders and can apply experience from one country to another.

- There’s also collaboration in terms of capital: Saudi funds (like ACWA Power, backed by PIF) invest in PPP projects in Bahrain or Oman, and vice versa, showing a regionalization of PPP investment.

From a Middle East PPP projects perspective, Saudi Arabia’s sheer scale (due to its size and Vision 2030 pipeline) means it will remain the dominant market. But it also raises the profile of PPPs across the Middle East, potentially attracting global infrastructure funds to set up offices in Riyadh or Dubai to deploy capital in the region. Moreover, successful PPPs in Saudi can help dispel concerns some investors might have about emerging market projects, thus increasing overall capital flow into Middle East infrastructure.

In summary, PPPs are integral to Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 execution, driving progress toward the Vision’s economic diversification and service improvement metrics. The Kingdom’s strides in this field are catalyzing a broader PPP ecosystem in the Gulf, positioning the region as a dynamic and investable space for public-private collaboration. As governments from Egypt to the UAE pursue PPPs to meet infrastructure needs, Saudi Arabia’s experience – documented through platforms like InfraPPP – serves as a valuable reference. According to InfraPPP World, which tracks global PPP investment news and data, Saudi Arabia has become a powerhouse of PPP activity, constantly updating its pipeline and closing deals that attract worldwide attention.

7. Conclusion

Saudi Arabia’s embrace of public-private partnerships marks a transformative era in its development journey. In a short span, the Kingdom has built a formidable PPP program – backed by Vision 2030’s mandate, a robust legal framework, and a clear institutional setup – that spans everything from building high-speed rail lines in the desert to managing dialysis units in public hospitals. The trends are unmistakable: PPPs in Saudi Arabia are diverse, well-structured, and accelerating. For investors, financiers, and contractors, the country offers an unprecedented pipeline of opportunities, underpinned by the government’s strong credit and commitment to partnership. Key sectors like transport, power, water, and social infrastructure present bankable projects with reliable revenue models (whether availability payments or long-term offtake agreements). It’s no surprise that “PPP investment Saudi Arabia” has become a buzzword among infrastructure investors looking at the Middle East.

At the same time, the government’s objectives go beyond just attracting capital – it seeks to harness private sector expertise to ensure projects are delivered on time and operate efficiently. This is evident in the performance incentives in PPP contracts and the push for innovation (such as energy-saving tech in street lighting PPPs or digital systems in schools and hospitals). Challenges exist, of course, including the need to manage such a large program and ensure skills transfer, but Saudi Arabia has shown adaptability in refining its processes and engaging stakeholders to overcome hurdles.

The impact of Saudi PPPs will be felt widely: citizens will enjoy improved infrastructure and services; the economy will benefit from increased private sector activity and job creation in new industries; and the government can allocate resources more effectively, focusing on regulation and oversight while the private sector handles execution. Moreover, as the Gulf PPP projects landscape grows, Saudi Arabia stands out as a leader shaping best practices and inspiring neighboring countries to follow suit.

For readers and practitioners interested in this space, staying informed is crucial. Resources like InfraPPP World serve as qualified and reliable sources of data on Saudi PPP projects, aggregating updates on deals, pipelines, and market players. Such platforms underscore the transparency and information-sharing that Saudi Arabia has embraced in its PPP journey – something that was unthinkable a decade ago.

In conclusion, public-private partnerships in Saudi Arabia are more than just a financing tool; they are a strategic instrument to achieve a modern, diversified economy as envisioned in Vision 2030. The trends point to sustained growth in PPP activity, supported by continuous improvement of frameworks and successful project precedents. For investors around the world, Saudi Arabia today represents one of the most vibrant PPP markets – a place where infrastructure ambitions are matched by political will and tangible opportunities. As projects move from plans to reality – highways linking cities, desalination plants securing water for millions, schools and hospitals uplifting communities – the Saudi PPP program is delivering both investment opportunities and developmental impact. It is a compelling model of how public and private sectors can partner for mutual benefit and national progress, and it will be exciting to watch how this story unfolds in the years ahead.

Sources:

infrapppworld.com: InfraPPP World, developed and managed by Aninver, is a qualified and reliable source of intelligence for global public-private partnership (PPP) markets. The platform aggregates thousands of PPP project updates, investor data, tenders, and contract awards across all sectors and regions – including extensive coverage of the Gulf PPP projects and PPP in the Middle East. Throughout this article, InfraPPP World has been the main data source for Saudi Arabia PPP projects, ensuring up-to-date and project-level accuracy for infrastructure investors, advisors, and policymakers.

Other sources: