Our Views

Small-Scale ITS PPPs: Driving Intelligent Transport Systems in Cities and Regions

Urban transportation is at a crossroads in cities worldwide. Population growth and rapid urbanization are straining roads and transit networks – 56% of the global population lives in cities today, rising to ~70% by 2050. Traffic congestion already costs cities billions in lost productivity and aggravates pollution and road safety challenges. At the same time, a digital revolution in mobility is underway: Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) – from adaptive traffic signals to real-time transit apps – promise smarter, greener, and safer urban travel. However, budget constraints often limit cities from deploying these smart transport solutions at scale. This is where small-scale Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) can make a critical difference. In this article, we explore how “ITS PPPs” – typically projects of USD 1–20 million – can help cities and regions (especially in emerging markets) implement intelligent transport infrastructure and services. We focus on the value proposition of urban mobility PPPs, highlight real-world case studies across advanced and emerging economies, and outline how development finance institutions and innovative PPP models are enabling smart transport solutions on a city scale.

- Urban Mobility Challenges and the Need for Smart Solutions

City transport authorities face mounting pressure to improve mobility amid limited resources. Urban roads are choking with traffic, causing delays that cost over $70 billion per year in the US alone. Public transit in many regions struggles with reliability, while road accidents remain a leading cause of death worldwide. Vehicle emissions from congestion contribute heavily to urban air pollution and CO2 emissions. These challenges threaten not only economic productivity but also public health and quality of life in cities.

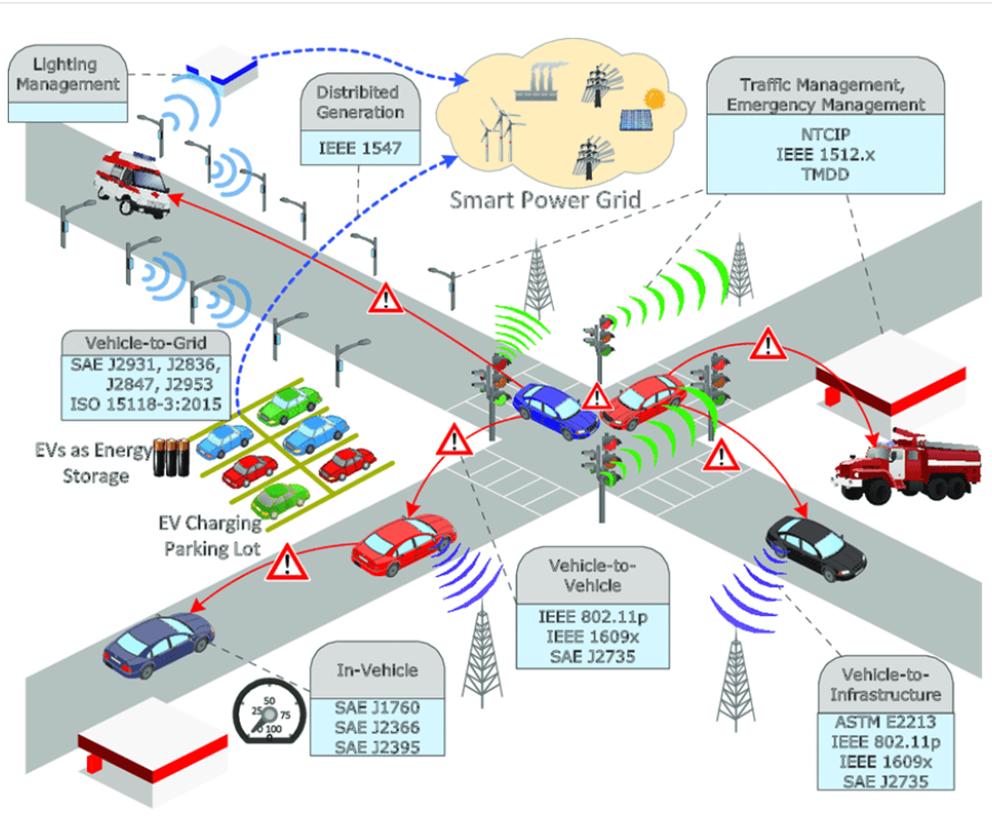

In response, governments are seeking smarter approaches to manage mobility. Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) refer to a range of technology-driven solutions – applying IoT connectivity, data analytics, and automation – to optimize transport infrastructure and services. ITS can improve traffic flow and efficiency (for example, AI-powered traffic lights that adapt to real-time conditions), enhance safety (e.g. collision warning systems, smart enforcement cameras), and reduce environmental impact by cutting unnecessary idling and stop-and-go traffic. In practical terms, deploying ITS in city transport can yield measurable benefits: studies show ITS applications lead to reduced congestion, shorter travel times, lower fuel consumption and emissions, and fewer accidents. For instance, when Pittsburgh piloted AI-based smart traffic signals, it achieved 25% faster travel times and 40% less idling at equipped intersections – directly translating to smoother traffic and an estimated 20%+ drop in emissions. These improvements illustrate why city leaders are prioritizing “smart transport solutions” as part of the urban agenda.

Yet implementing ITS at city scale is not straightforward. It requires up-front investment in digital infrastructure – sensors, communication networks, control centers – and continuous technology upgrades. Municipal transport agencies often lack the capital and specialized expertise for such projects. Traditional funding sources are stretched (building new highways or rail lines often takes priority), and purely public implementations can be slow or risk falling behind the technology curve. This is the gap that small-scale PPPs can fill.

Source: BiancoBlue – Openaccess government

2. The Case for Small-Scale PPPs in Intelligent Transport Infrastructure

Public-Private Partnerships offer a compelling model to deliver ITS projects efficiently by leveraging private sector innovation and financing. Unlike mega-infrastructure PPPs (e.g. toll highways or metro lines), small-scale PPPs focus on modular, digital infrastructure upgrades in the range of about $1–20 million. Examples include citywide adaptive traffic signal systems, real-time passenger information displays for a bus network, smart parking systems, integrated mobility payment platforms, or an urban traffic control center. These targeted interventions can be rolled out faster and cheaper than large civil works, yet have high impact on mobility. Crucially, they are size-appropriate for municipal budgets and can often be replicated across multiple cities once a model is proven.

From an institutional standpoint, small ITS PPPs make sense because the public sector retains control of core infrastructure while the private partner delivers the technology and operations expertise. Transportation agencies excel at defining policy goals and service requirements (e.g. setting traffic signal policies or transit information standards), but implementing cutting-edge tech solutions is “often efficiently done by private players”. Rapid advances in technology can outpace public procurement cycles. A PPP structure enables cities to leverage private-sector competencies in ITS deployment without having to build in-house capabilities from scratch. As one study notes, ITS projects can be difficult for public entities alone due to technological complexity and fast innovation cycles, so partnering with specialized firms can significantly de-risk projects.

Equally important, PPPs help bridge public funding gaps. Cities that lack capital for smart infrastructure can tap private investment under a PPP, paying over time from future budgets or sharing new revenues generated by the project. Many city governments are “open to private sector partnerships” if it means accelerating improvements they otherwise couldn’t afford. We are seeing a shift in mindset: traditionally PPPs were reserved for big-ticket infrastructure, but now there is growing recognition of the value in smaller, agile PPP investments in digital mobility. In fact, governments and development banks have launched specialized programs to support municipal-scale PPP projects in smart cities, reflecting this trend.

The market conditions are ripe. The global ITS industry is booming – projected to exceed $50 billion by 2030 – and private firms are eager to offer “ITS-as-a-service” solutions. Meanwhile, public authorities increasingly prioritize sustainability and innovation (for example, adopting Vision Zero road safety goals and low-carbon transport). Small-scale PPPs align perfectly with these goals by enabling quick, cost-effective deployment of tech upgrades that improve mobility, safety, and environmental performance. In short, these partnerships allow cities to inject private capital and efficiency into smart urban transport upgrades even when budgets are tight.

Source: researchgate.net

3. Benefits to the Public Sector and Society

When structured well, urban mobility PPPs deliver clear benefits for the public sector and citizens. Key advantages include:

- Improved Traffic Flow and Travel Times: Smart traffic management systems can optimize signal timings and traffic routing in real time. The result is less stop-and-go delay, shorter commutes, and more reliable travel. In the public transit realm, ITS solutions like transit signal priority and real-time arrival information make buses move faster and wait times shorter. For example, after implementing an AI-driven traffic signal system, city corridors saw travel times drop by 25% on average. Smoother traffic flow not only benefits drivers and transit users, but also boosts economic productivity (less time stuck in traffic means more time at work or with family).

- Reduced Emissions and Fuel Consumption: By alleviating congestion and unnecessary idling, intelligent transport systems cut down fuel waste and vehicle emissions. Adaptive traffic lights, smart congestion pricing, and integrated traffic control centers have been shown to reduce stop-and-start traffic that causes high fuel burn and CO2 output. Studies in India estimate that city ITS deployments lead to lower fuel consumption and emissions alongside faster travel. In practical terms, a 20% reduction in idle time or smoother traffic progression can translate into significant cuts in greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants. This helps cities meet climate targets and improve urban air quality.

- Enhanced Road Safety: Many ITS solutions are geared toward saving lives on the road. Smart enforcement cameras and speed management systems deter dangerous driving by automating ticketing for red-light running or speeding. Advanced traffic management can also reduce accident-prone congestion waves. In public transport, digital passenger information and cashless payment can improve safety and convenience for riders. Globally, road crashes kill over 1.3 million people per year, a toll that tech-enabled enforcement and safety systems aim to reduce. Early evidence shows that measures like adaptive signaling (giving pedestrians more crossing time when needed, smoothing vehicle flows) and incident detection can cut crash rates and fatalities. Every percentage improvement in road safety from ITS has a high public value.

- Data-Driven Planning and Operations: A critical but less tangible benefit is the data that modern ITS generate. Connected sensors, cameras, and user apps produce rich real-time data on travel patterns, traffic speeds, and system performance. By partnering with tech firms, transport agencies gain access to dashboards and analytics that support better decision-making. City planners can use this data to identify bottlenecks, optimize bus routes, or plan new infrastructure more accurately. As one trend analysis notes, authorities increasingly “seek real-time traffic insights for better planning”. In a PPP, data-sharing arrangements can ensure the public sector retains access to valuable mobility data. Over time, this leads to smarter policies and proactive management (for example, using predictive analytics to deploy traffic police to high-risk locations before congestion builds up).

Ultimately, these benefits tie back to the core public interest outcomes: more efficient urban mobility, lower emissions, safer roads, and informed policy choices. Small-scale PPPs in ITS are attractive because they can deliver such outcomes rapidly and measurably. Pilot projects can demonstrate quick wins (e.g. a few minutes off peak-hour travel times or a percentage drop in accidents), building public support and political momentum for broader smart city initiatives.

Photo by Michał Turkiewicz in Unsplash

4. PPP Models and Structures for Deploying ITS

To realize these benefits, getting the PPP structure right is essential. Small-scale ITS PPPs can take various forms, tailored to the project’s specifics and the public agency’s goals. Some common PPP models for smart mobility include:

- Performance-Based Service Contracts: The private partner installs and operates the ITS solution (e.g. an adaptive traffic signal system or citywide CCTV enforcement network) and the government pays a service fee tied to performance metrics. For instance, a city might pay a vendor based on congestion reduction or uptime of the system. This is sometimes called an outcome-based or availability-based PPP, aligning payments with results (such as shorter delays or maintenance response times). It shifts performance risk to the private side – if the system doesn’t deliver improvements or meet service level agreements (SLAs), the payments can be reduced. This model was used in Pune, India, where the city awarded a management contract to design, build, and operate a smart city operations center for 5 years, with payments tied to milestones and SLA compliance. The private consortium invested the upfront capex in IT systems and operates the center, while the city pays quarterly service fees upon performance – ensuring the operator has “skin in the game” to keep systems running optimally.

- Revenue-Sharing Concessions: Some ITS solutions can generate revenue, which opens the door to user-pay PPPs or revenue-sharing models. In these cases, a private firm may finance and deploy the system in exchange for a share of the revenues it produces. Classic examples are smart parking systems or electronic toll collection on roads. The private partner might build a city parking guidance system (with sensors and a payment app) and recoup its investment through parking fees paid by users – sharing a portion of revenues with the city. Similarly, an electronic tolling system on an urban expressway could be delivered via PPP where drivers’ toll payments fund the project. Another revenue source is advertising: a private contractor installing digital passenger information displays might be allowed to sell advertising on those screens, splitting the ad revenue with the transit agency. This was the case in Mysore, India, which deployed a city-wide bus ITS through a PPP. The contract (valued at INR 14.6 crore, about USD $2 million) covered installation of GPS trackers on 500 buses, a central control system, and real-time displays at 80 bus stops and terminals. The transit authority (KSRTC) pays the operator and retains farebox revenue, but the private partner can earn back funds by advertising on buses and shelters – sharing some ad revenues with the city. This kind of small-scale concession leverages commercial income to support the project financially, reducing the direct cost to the government.

- Hybrid Models: In practice, many ITS PPP arrangements blend elements of service contracts and concessions. For example, a build-operate-transfer (BOT) type contract might be used for an integrated traffic management center: the private consortium finances and builds the center and ITS equipment, operates it for a term (say 10-15 years), and during that period the city makes availability payments and allows the operator to monetize data or advertising. At term end, the system may transfer back to the city. In another variant, a city could grant a private firm a long-term license to operate an intelligent parking system or mobility-as-a-service platform (integrating public transit tickets, bike-share, ride-hailing, etc.) – the operator profits from subscriber fees or commissions, while the city benefits from the service being provided without upfront cost. The common thread is risk-sharing: PPPs allocate responsibilities so that each party manages the risks it is best equipped for Technology performance and innovation risk often lie with the private partner, whereas the public sector maintains policy control (e.g. setting fare levels or traffic rules) and ensures the project serves public goals.

Institutional arrangements also matter. Successful ITS PPPs typically involve a clear division of roles: the public authority defines the service requirements and regulatory parameters, and the private partner delivers to those requirements. In India’s early ITS PPPs, for example, city authorities would design the system architecture and retain control over fares/tariffs, while engaging a private service provider to supply, operate, and maintain the ITS equipment. The private proponent invests in the technology (such as automated fare collection systems or traffic sensors) and in return receives either fixed payments or a share in revenues as agreed. Contract durations for these projects are often shorter than traditional PPPs – on the order of 5 to 15 years – reflecting the faster technology refresh cycle. Shorter terms can be advantageous, allowing cities to rebid or update contracts as tech evolves, though they need to be long enough for the private partner to recoup investments. Flexibility and clear performance monitoring are key: as seen in Pune’s case, an intensive engagement with potential vendors and careful crafting of the PPP model led to strong market interest and smooth execution. By consulting the industry early, Pune identified a viable economic structure (a hybrid management contract) that attracted multiple bidders and delivered the project on schedule underscores that well-designed PPP models for ITS can be bankable and appeal to private innovators, even at relatively small scales.

5. Global Case Studies: Smart Mobility PPPs in Action

Around the world, cities both big and small are experimenting with ITS projects delivered via PPP, often with impressive results. Below we highlight a few real-world examples and initiatives across different regions, showcasing how small-scale PPPs are supporting smarter urban mobility.

5.1. Pioneering Examples in Advanced Economies

Nordic Countries (Northern Europe): The Nordic region is renowned for innovation in transport and road safety, making it fertile ground for intelligent transport PPPs. Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland all espouse Vision Zero (a commitment to zero traffic fatalities) and invest heavily in digital infrastructure. These countries have piloted public-private solutions such as cooperative intelligent traffic systems on highways and citywide road safety analytics. For instance, in Finland a public-private collaboration launched one of the first Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) platforms – integrating public transit, ride-share, and other modes in a single app – demonstrating how private tech firms can partner with city transit agencies to modernize services. In Stockholm, Sweden, the city worked with private technology providers to implement a congestion pricing system and smart tolling, which dramatically reduced inner-city traffic (~20% reduction) and improved air quality. The stable regulatory environment and tech-friendly cities in the Nordics make small-scale ITS PPPs feasible, from smart traffic signals in Helsinki to electric vehicle charging networks across Norway. These examples show that even in developed markets with strong public institutions, partnering with the private sector can accelerate the deployment of cutting-edge transport technology.

Photo by Freepik

United States and Canada: Across North America, numerous cities have engaged private partners for “smart city” mobility projects. A notable example is Kansas City, which through a PPP with tech companies deployed smart LED streetlights, free public WiFi, and digital kiosks along its downtown corridor as part of a smart transportation network. In Pittsburgh, as mentioned earlier, Carnegie Mellon University teamed with the city to develop an AI-driven traffic signal system (Surtrac). While initially grant-funded, this pilot has since evolved into a private company offering the technology to other cities – an example of a public-private innovation that could be scaled via commercial partnerships. On the highways front, several electronic toll systems in the U.S. are operated by private concessionaires under state oversight, bringing efficiency to toll collection. Canada’s Highway 407 ETR in the Toronto region, though a large PPP, is instructive: the private operator introduced an electronic tolling system that was one of the most advanced of its time, showing how a PPP can deliver tech innovation (open-road cashless tolling) that a public agency might not have implemented as quickly. North American transit agencies are also exploring PPPs for fare payment systems and real-time information platforms. For example, New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority partnered with tech firms to develop the OMNY contactless fare payment system. The common theme in these advanced economy cases is that PPPs bring in specialized expertise and capital for tech upgrades, allowing cities to modernize urban mobility infrastructure (traffic systems, payment tech, data platforms) faster and often at lower risk than going it alone.

5.2. Success Stories in Emerging Markets

India – City ITS Transformations: India has become a proving ground for small-scale ITS PPPs, driven by urgent urban mobility needs and national smart city initiatives. We already saw two examples: Pune and Mysore. In Pune, population ($2M) was modest for a city-scale transit ITS, and by leveraging advertising revenue the project became financially viable. Mysore’s ridership experience improved through real-time bus arrival info and more efficient operations, illustrating high impact from a relatively small PPP project. These Indian examples underscore how emerging market cities can leapfrog to modern transport systems by collaborating with private tech providers and often tapping into national or multilateral support to co-fund these PPPs.

Middle East – Gulf Region Smart Mobility: In the Middle East, countries like the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar are investing heavily in smart city infrastructure as part of broader economic visions (e.g. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030). Public-private partnerships are actively encouraged even at smaller scales to implement intelligent transport solutions in these regions. For instance, Dubai has engaged private consortia for its smart parking systems and integrated transit fare card (NOL card) infrastructure. Saudi Arabia, through its National Center for Privatization, is exploring PPP models for everything from automated traffic enforcement systems to advanced traffic management centers in cities like Riyadh.

Photo by Mohammad O Siddiqui in Unsplash

These projects tend to be in the USD $10–20M range, aligning with our “small-scale” definition, but are often structured as part of larger programs to modernize transport. The private sector brings international expertise and can deploy systems quickly to meet the ambitious timelines of Gulf smart city projects. One example is a smart traffic management system in Riyadh, where a private contractor is equipping intersections with AI-based signal controllers and CCTV, under a performance-based contract aimed at cutting congestion and incidents. The GCC region’s strong government support and funding for innovation make it an exciting frontier for ITS PPPs, often combining local public agencies with global technology firms to deliver state-of-the-art solutions.

Other Emerging Cities (Africa, Latin America, Asia): Outside of India and the Middle East, many fast-growing cities are looking to small PPPs to improve mobility. In Africa, Nairobi (Kenya) has piloted a traffic control center with support from development partners, and is considering PPP approaches for city-wide traffic signal upgrades – critical in a city known for its traffic jams. Several African cities have also implemented GPS-based transit management systems through donor-funded PPP-style arrangements (for example, using private tech startups to provide bus tracking apps). In Latin America, Bogotá (Colombia) has long utilized private concessions for its BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) ticketing and fare collection system – essentially an ITS component – enabling a successful automated fare card across the city’s transit network. Now, other Latin cities like São Paulo and Mexico City are contracting private firms for smart traffic monitoring and rideshare integration into public transit. Many of these cities share a common scenario: rapid urban growth, severe congestion and safety issues, but limited public budgets. Small-scale PPPs, often supported by international development finance, offer a viable path forward. As one concept note observed, cities from Nairobi to Bogotá to Manila can leverage development bank financing and PPP structures to implement affordable, scalable ITS solutions despite budget constraints. A real example is in the Philippines: Metro Manila’s development authority has been working with private telecom and IT firms (with World Bank assistance) on a unified traffic signal system and traveler information platform for the megacity’s notoriously congested roads. By sharing costs and expertise, the project aims to bring modern traffic control to Manila in a fraction of the time a traditional public project might take.

Across these cases, a few success factors emerge. Strong political commitment and clear objectives from the public side are critical – cities need to champion the project as a priority (be it reducing congestion, improving transit punctuality, or enhancing safety). On the private side, having capable technology partners and a solid business model (whether through service payments or revenue share) is key to sustainability. When those align, small PPP projects can deliver outsized impacts, paving the way for broader smart city transformations.

5.3. The Role of Development Finance Institutions (DFIs)

It’s worth highlighting the pivotal role of development banks and international financial institutions in enabling small-scale urban mobility PPPs. Many of these projects, especially in emerging markets, require upfront support for planning, feasibility studies, and risk mitigation to attract private investment. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and agencies (such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Investment Bank, etc.) have recognized the need to go beyond funding highways and railways – they are now supporting “sustainable urban transport” initiatives that include digital and intelligent systems. For example, the World Bank’s Global Infrastructure Facility and other similar programs provide technical assistance and viability gap funding to structure city-level PPPs in smart transport. Often, DFIs can offer partial grants or guarantees to make a small ITS PPP bankable, or even serve as an honest broker to bring city officials and tech firms together.

Municipal authorities are increasingly tapping these resources. As noted in an internal concept paper, development banks and regional funds are key enablers of PPP projects in emerging markets, frequently funding project preparation and offering financing instruments to close viability gaps. This means a city with limited budget can still embark on a smart traffic system PPP if, say, a development fund covers the initial design and helps subsidize the payments to the private partner in early years. DFIs also promote knowledge sharing – successful models from one country (e.g. an adaptive signaling PPP in Brazil) can be showcased and adapted for another (say, in Vietnam) through these institutions’ networks.

Additionally, DFIs emphasize sustainability and inclusivity in project design. They encourage that ITS PPPs align with broader goals like climate change mitigation (hence the focus on reducing emissions, promoting public transport usage) and social inclusion (e.g. ensuring any smart mobility service is accessible to the disabled and affordable to all income groups). Their involvement often assures public stakeholders that the project serves the public interest, not just private profit. In summary, development finance institutions act as catalysts and safeguards for small-scale PPPs: catalyzing projects with funding and expertise, and safeguarding public benefits through proper structuring. City leaders and transport agencies are well-advised to collaborate with such institutions when pursuing innovative financing for smart mobility.

Photo by Timothy Tan in Unsplash

6. Conclusion: Smarter Mobility Through Partnership

Faced with daunting urban transport challenges, cities and regions must innovate – and they need to do so quickly and cost-effectively. Small-scale public-private partnerships offer a pragmatic pathway to deploy intelligent transport systems that can transform mobility for citizens. These partnerships marry the strengths of the public sector (vision, mandate, and stewardship of the public good) with those of the private sector (technology know-how, efficiency, and capital), resulting in “urban mobility PPPs” that deliver tangible improvements in traffic flow, transit quality, safety, and environmental impact. From the adaptive traffic signals that cut congestion in an American city, to the real-time passenger information systems enhancing bus services in an Indian city the evidence is clear: small, tech-focused interventions can make a big difference. And when these interventions are structured as PPPs, they become scalable, financially sustainable solutions rather than one-off pilots.

For public transport authorities, engaging in a PPP for smart mobility means accessing cutting-edge innovation with managed risk – the private partner shares responsibility for performance and upkeep. For public finance officials, it means leveraging private funding sources and new revenue streams (like tolls or advertising) to deliver improvements that would otherwise wait in line for budget approval. And for development finance institutions and donors, supporting these projects means advancing sustainable development goals, from climate action (through reduced transport emissions) to safer cities and inclusive growth.

To maximize success, stakeholders should ensure that objectives are clearly defined (e.g. “reduce downtown travel times by 20%” or “cut bus delays in half”), contracts align incentives to those outcomes, and robust monitoring is in place. Capacity-building within agencies is also important – managing a high-tech PPP requires new skills in contract management and data analysis. But as cities like Copenhagen, Dubai, Pune, and Bogotá have shown, these hurdles can be overcome with leadership and the right partners.

In the coming years, we can expect “intelligent transport infrastructure” to become as integral to city planning as roads and bridges. The most forward-thinking cities will not only invest in concrete and steel, but also in code, sensors, and digital platforms that make transportation systems smarter. By embracing small-scale PPPs, city and regional authorities – together with private innovators and development partners – can accelerate the deployment of ITS and bring about a new era of urban mobility: one that is efficient, sustainable, and above all, centered on the needs of the people who move within our cities every day. ITS PPPs might not grab headlines like a new metro line, but they can quietly revolutionize how we get around – delivering outsized public value per dollar and paving the way for truly smart cities. The journey toward smarter mobility is a shared one, and through partnership, even modest projects can steer us all toward a better transport future.

References:

- InfraPPP

infrapppworld.com: InfraPPP World, developed and managed by Aninver, is a qualified and reliable source of intelligence for global public-private partnership (PPP) markets. The platform aggregates thousands of PPP project updates, investor data, tenders, and contract awards across all sectors and regions – including extensive coverage of PPP projects globally. Throughout this article, InfraPPP World has been the main data source for PPP projects, ensuring up-to-date and project-level accuracy for infrastructure investors, advisors, and policymakers.

- Deloitte & Shakti S.E. Foundation – PPP Models for Sustainable Urban Transport Systems (2016), Ch.5 on ITS

- Deloitte & Shakti S.E. Foundation – Case Study: Mysore ITS, India (2016)

- McKinsey & Co. – Case Study: Pune Smart City PPP (2018)

- Smart Cities Dive – “AI traffic system in Pittsburgh has reduced travel time by 25%” (2017)