Our Views

Agribusiness Innovation: Technology for Rural Productivity and Inclusion

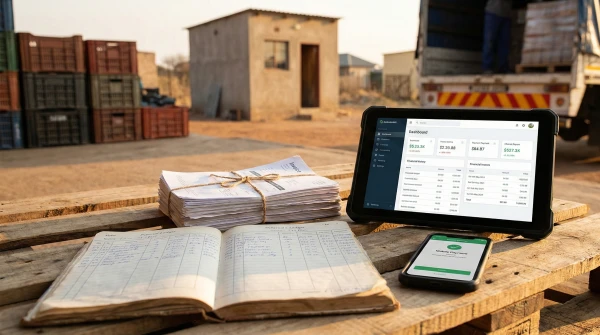

Agricultural ecosystems in developing countries face complex challenges – from low productivity and market isolation to climate change and rural poverty. Agribusiness innovation offers a way forward by harnessing technology, promoting sustainability, and fostering rural economic development in tandem. When agriculture and agribusiness work in synergy, they can spur economic growth, food security, poverty reduction, and community empowerment, forming the backbone of rural development. This article explores how technological innovations, sustainable practices, and inclusive rural development strategies reinforce each other to strengthen agricultural ecosystems. It draws on insights from the white paper “Agribusiness Innovation: Technology for Rural Productivity and Inclusion” and real-world examples from Aninver’s consulting work in Panama, Liberia, the G5 Sahel, and Tunisia. The key lesson: an integrated, context-sensitive approach is essential for transforming rural agriculture into a resilient, inclusive engine of prosperity.

Technology as a Driver of Productivity and Inclusion

Modern technology is revolutionizing farming across the developing world. Digital tools and connectivity allow even remote smallholders to access information, financial services, and markets that were once out of reach. For example, mobile applications now deliver weather forecasts, crop advice, and market prices to farmers’ phones, helping them make informed decisions. In Panama, a new program is strengthening institutional capacities for digital monitoring and data-driven decision-making in agriculture. By digitizing extension services and using an online Monitoring, Adjustment, and Learning framework, extension agents can track farmers’ progress and adapt support in real time. Such innovations ensure that technology benefits rural communities and improves outcomes on the ground.

Equally important are precision agriculture and mechanization tools that boost efficiency. Remote sensing via drones or satellites, GPS-guided farm machinery, and Internet-of-Things (IoT) sensors are no longer science fiction on small farms. For instance, Aninver’s agribusiness projects have leveraged remote sensing, IoT soil sensors, and farm management software to make farming more data-driven. These technologies allow farmers to optimize fertilizer use, detect crop stress early, and irrigate more precisely – improving productivity while building climate resilience. In one initiative, AI-driven irrigation scheduling significantly cut water usage on almond farms without sacrificing yields. This illustrates how tech innovation can create “win-wins,” raising output and profitability even as it conserves resources.

However, technology alone is not a silver bullet. There is a risk of a digital divide leaving behind those without access or skills. As the research emphasizes, digital technology should not create new barriers for people without devices or digital abilities; any tech rollout must be accompanied by training and inclusion efforts. In practice, this means pairing high-tech solutions with capacity building on the ground. Panama’s program, for example, trains young “innovation links” – local youth who mentor fellow farmers in using improved techniques and digital tools. This human link ensures that even less tech-savvy farmers can adopt new practices effectively. More broadly, supportive infrastructure (like rural internet connectivity) and enabling policies are needed so that innovations can take root. A key takeaway from global experience is that frameworks and policies must support agricultural modernization, technology adoption, and capacity creation, alongside investments in infrastructure and education. When those conditions are met, technology becomes a powerful driver of inclusion – connecting farmers to knowledge, financial services, and markets they could never access before – ultimately narrowing rural-urban gaps.

Sustainable Farming and Climate-Resilient Practices

Sustainability is the second crucial pillar of stronger agricultural ecosystems. Many developing countries’ farmers are on the frontlines of climate change, facing erratic rainfall, droughts, and land degradation. Thus, boosting productivity cannot come at the expense of the environment – in fact, long-term productivity depends on conserving soil, water, and biodiversity. Sustainable farming practices, often referred to as climate-smart agriculture, seek to balance these needs by increasing yields while safeguarding natural resources.

One effective approach is the adoption of agroecological practices – techniques that work with natural ecosystems (crop diversification, agroforestry, organic soil management, etc.) to improve resilience. In Panama, the Sustainable Productive Innovation component of a national program is promoting agroecological and climate-resilient farming systems through demonstration farms and technical assistance. Thousands of smallholder families are being supported in transitioning to practices like organic fertilization, drought-tolerant crop varieties, and improved soil conservation that enhance productivity while preserving the environment. This has a dual benefit: farmers see better harvests and incomes, and their farms become more resilient to climate shocks such as floods or drought.

Sustainability also involves tackling land degradation and resource scarcity head-on. In parts of Africa’s G5 Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Chad), decades of overuse and harsh climate have led to severe soil erosion and water shortages. Agriculture and the environment are deeply interlinked in such fragile regions – drought and degraded land exacerbate social fragility, and vice versa. A recent Africa-specific study in the Sahel found that restoring land fertility and improving water access are not just environmental goals but also critical for stability and livelihoods. The study provided policy recommendations on making agriculture projects “fragility-sensitive,” ensuring that interventions (like introducing drought-resistant crops or water-harvesting techniques) are tailored to reduce conflict risks and bolster community resilience. The lesson is clear: context-sensitive sustainable practices are vital. What works in one ecosystem (say, drip irrigation in semi-arid regions) might differ in another (e.g. floodwater farming in floodplains), but the principle of aligning farming with ecological realities holds everywhere.

Finally, sustainability in agriculture benefits greatly from technology – coming full circle to our first theme. Innovations such as solar-powered irrigation, biofertilizers, or apps that inform farmers of climate-smart techniques accelerate the adoption of sustainable practices. For instance, precision farming tools like AI-guided irrigation not only improve yields but also cut resource use, making farms more resilient to climate variability. In summary, integrating sustainability into agribusiness innovation is no longer optional; it is an imperative for long-term rural productivity and food security. Farmers who embrace climate-resilient practices today are investing in the future health of their land and communities.

Rural Economic Development and Inclusive Value Chains

Technology and sustainable farming will have limited impact unless rural communities can translate productivity gains into economic opportunity. This is where rural economic development initiatives – especially those focusing on markets, value addition, and inclusive growth – play a pivotal role. Strengthening an agricultural ecosystem means not just growing more crops, but ensuring farmers can earn a decent living from those crops. That requires building bridges from the farm to the broader economy.

One critical strategy is developing agricultural value chains that connect small producers with markets, agro-industries, and consumers. Too often, smallholder farmers in developing countries are isolated – they sell raw produce at farm gate for little profit, lacking access to processing facilities or lucrative markets. Agribusiness innovation addresses this by organizing farmers into cooperatives, improving rural logistics, and attracting investments in processing and storage. For example, Panama’s program has an Inclusive Market Innovation component that helps farmers and rural youth develop business plans, reduce post-harvest losses, and access higher-value markets. By improving basic practices (like better on-farm storage to avoid spoilage) and linking producers to buyers or agro-processors, these efforts enable farmers to capture more value from what they produce. It also means diversifying products – moving from just selling unprocessed staples to maybe processing fruits into jams or milk into cheese – thereby increasing incomes and rural employment.

Entrepreneurship and SME development in rural areas further fuel economic growth. When rural people are given the information, tools, and opportunities to engage not just in farming but also in agribusiness (like running a small food enterprise or farm input supply business), they can take control of their own development and build resilient, self-sufficient communities. Across many countries, we see the rise of “agripreneurs” – innovative farmers or youth-led startups offering agri-services, from farm drone services to mobile crop marketplaces. Supporting these grassroots innovators through training, mentorship, and access to credit yields a double benefit: job creation for rural youth and more innovation in the local agricultural sector. In Tunisia, for instance, the World Bank-funded TRACE program (Tunisian Rural and Agricultural Chains of Employment) explicitly aimed to boost agricultural competitiveness while stimulating rural employment for youth and women. Such programs recognize that engaging the energy of young entrepreneurs (and empowering women farmers) can transform the rural economy from within, making it more dynamic and inclusive.

Policy and institutional support are also key to rural economic development. Governments need to create an enabling environment – through rural infrastructure (roads, electricity, broadband), supportive regulations, and investment in research and extension – so that innovations can flourish. In Liberia, an innovative capacity-building project tackled an often overlooked aspect: the agricultural tax and policy framework. Consultants worked with the Liberia Revenue Authority to analyze the agriculture sector’s role in the economy and to design a fiscal regime for taxing the largely informal small-scale farming sector. By training tax officers and recommending policy changes, the project sought to bring more of the farm economy into the formal system in a fair way, ensuring the government can reinvest revenues in agricultural services. This example underlines that strengthening agricultural ecosystems isn’t just about on-farm activity – it extends to good governance, institutions, and rural finance. When farmers have secure land rights, reasonable taxes, access to credit, and government support, they are far more likely to invest in improving their operations and participating in the market economy.

In summary, rural economic development efforts tie everything together by creating the conditions for farmers to thrive economically. Market access, value chain integration, rural finance, and entrepreneurship all contribute to turning agricultural potential into improved livelihoods. They also diversify rural economies beyond subsistence farming alone. Studies have noted that diversification into agribusiness, services, and microenterprises spreads economic risk and taps the latent potential of rural populations, making communities less vulnerable and more prosperous. Ultimately, the goal is an inclusive rural transformation – one where even small family farms are connected to markets, contributing to national growth and sharing in the gains.

Key Lessons and Context-Sensitive Strategies

Experience from various developing countries shows that successful agricultural ecosystem strengthening requires a holistic and context-sensitive approach. Technology, sustainability, and economic development are mutually reinforcing – but only if implemented with careful attention to local realities. Here are some key lessons and strategies for practitioners and policymakers:

- Blend Innovation with Capacity Building: Simply introducing high-tech tools or new farming methods is not enough – human capacity must be built to use them effectively. Training programs for farmers, extension agents, and local institutions are essential. For example, in Panama’s project, hundreds of rural extension agents were trained and supervised as “innovation facilitators” to help family farmers adopt new practices. Empowering people with skills and knowledge ensures innovations take root and last.

- Adopt Climate-Smart, Sustainable Solutions: Every agricultural development initiative today should integrate sustainability from the start. Practices that conserve soil, water, and biodiversity make farming communities more resilient to shocks. Projects should promote adaptive techniques (drought-resistant crops, agroforestry, water-saving irrigation) tailored to the local climate. This not only safeguards the environment but also protects long-term productivity and livelihoods.

- Foster Inclusive Value Chains: Strengthening farm ecosystems means connecting farmers to markets. Initiatives should build market linkages, value addition, and rural entrepreneurship opportunities. Whether through cooperatives, contract farming, or agro-processing hubs, helping farmers climb the value chain will increase their incomes. Inclusive business training (like Panama’s market innovation plans) and removing bottlenecks (like Liberia’s policy reforms) enable small producers to participate in profitable markets.

- Ensure Policy Support and Institutional Strengthening: Government and institutional backing can make or break rural initiatives. Successful programs often work closely with local authorities (e.g. agricultural ministries, research institutes) to align with national strategies and build institutional capacity. Strengthening local institutions and knowledge systems – as was done by enhancing coordination between Panama’s IDIAP and the Ministry of Agriculture for digital data systems – helps embed innovations into the public sector for sustainability. Policy frameworks should encourage innovation (through supportive regulations, tax incentives, or subsidies for climate-smart tech) rather than hinder it.

- Use Data and Continuous Learning: Robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) should be built into projects to track progress and allow adaptive management. Setting up baseline studies, as in Tunisia’s TRACE program, and conducting mid-term evaluations help identify what works and what needs adjustment. Feedback loops (such as Panama’s Monitoring, Adjustment, and Learning system) create a culture of continuous improvement. Data-driven insights enable scaling up successful interventions and course-correcting underperforming ones, thereby maximizing impact through learning.

- Tailor Strategies to Local Context and Fragilities: Perhaps most importantly, there is no one-size-fits-all model. Interventions must be sensitive to each community’s socio-economic and environmental context – whether it’s a post-conflict region, a drought-prone savannah, or an isolated mountain valley. In the G5 Sahel, for example, the African Development Bank emphasized fragility-sensitive programming, training its teams on how conflict and fragility interplay with agriculture. Understanding local culture, power dynamics, gender roles, and risks leads to solutions that communities can embrace. Participatory approaches – involving farmers in planning and decision-making – further ground projects in reality and boost community ownership.

Overall, integrating these lessons creates a virtuous cycle: technology and innovation drive productivity; sustainable practices ensure that gains are not short-lived; and economic development initiatives turn agricultural output into improved livelihoods and reinvestment, which in turn fuels further innovation. Success stories repeatedly show that when small farmers are given the right tools, training, and market opportunities, they “take control of their own development” and their communities become more resilient, successful, and self-sufficient. The path to strengthening agricultural ecosystems lies in this balanced approach – marrying the power of innovation with the wisdom of sustainability and the inclusivity of broad-based rural development.

Explore Related Projects by Aninver

If you’re interested in seeing these principles applied in practice, we invite you to explore some of Aninver’s projects that delve deeper into agritech, sustainability, and rural development in action:

- Family Agriculture Technical Assistance Project – Region 1, Panama – An IDB-financed initiative under Panama’s PIASI program that supports thousands of family farmers in improving productivity, climate resilience, and income through training, participatory planning, and a digital monitoring system.

- Agriculture capacity building & training for Liberia Revenue Authority's NRTS – A short-term project with the African Development Bank to strengthen Liberia’s Revenue Authority. It reviewed the agriculture sector’s contribution to the economy and trained tax officials in designing a fiscal framework to integrate small-scale farmers into the formal tax system, with policy recommendations for a more supportive business environment.

- Agriculture, biodiversity, land degradation and fragility in G5 Sahel – A knowledge and technical assistance project covering Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Chad. It examined how land degradation, drought, and agriculture intersect with social fragility, provided fragility-sensitive policy guidelines, and developed training for practitioners to incorporate resilience into agricultural programs.

- Impact Evaluation of the Tunisian Rural and Agricultural Chains of Employment Program (TRACE) – A rigorous evaluation of Tunisia’s “Rural and Agricultural Chains of Employment” program (TRACE) aimed at boosting agribusiness competitiveness and rural jobs. The project established a baseline, conducted mid-term and final evaluations, and used data-driven methodologies to measure how TRACE improved youth and women’s employment and agricultural value-chain integration, ensuring accountability and learning for future rural initiatives.

Each of these projects offers rich insights and lessons learned in real-world settings – from tropical Latin America to Sub-Saharan Africa. They illustrate the diversity of approaches needed to strengthen agricultural ecosystems. We encourage readers interested in rural development, public policy, or agritech to dive into these cases for a deeper understanding of what works and why. By learning from such experiences and supporting initiatives that integrate technology, sustainability, and inclusive development, you can be part of the movement to empower farming communities and secure a more resilient future for agriculture.

Ready to explore more? Check out Aninver’s project pages and publications for detailed reports and success stories, and consider how you might apply these insights or collaborate on similar initiatives. The challenges are great – but with innovation, commitment, and context-aware strategies, so are the opportunities for impact.