Our Views

Cultural PPPs: Museums, Audiovisual Hubs and Creative Centers Without Structural Deficits

Public cultural institutions like museums, creative industry hubs, and audiovisual production centers are cornerstones of heritage and creativity – yet they often struggle financially. Many such venues face structural deficits, meaning their operating costs consistently outpace revenues. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) offer an innovative solution by tapping private capital and expertise to support cultural infrastructure. This report investigates how PPP models can be applied to cultural projects to achieve long-term financial sustainability. It explores the rationale for cultural PPPs, the challenges of revenue generation in the arts, international success stories, innovative revenue mechanisms (from ticketing to digital monetization), governance and risk-sharing frameworks, and alignment of cultural PPPs with urban development and tourism. In the final section, we highlight examples of projects where Aninver has contributed to cultural PPP initiatives in emerging markets.

Why PPPs for Cultural Infrastructure?

Applying PPP models to cultural projects is driven by a simple rationale: bridging the gap between ambitious public cultural goals and constrained public budgets. Around the world, governments have turned to PPPs as “an efficient and sustainable way of financing public services and projects”. Cultural infrastructure – museums, theaters, heritage sites, creative industry centers – often requires large upfront investment and ongoing maintenance that governments alone struggle to fund. According to the International Project Finance Association, “in many countries the financing requirements of current and prospective infrastructure needs far outstrip available resources”. Cultural projects are no exception; they compete with pressing needs in health, education, and transport for public funds. PPPs provide a viable alternative by mobilizing private investment to finance costly infrastructure and share the burden of operating large cultural venues.

Equally important, PPPs can improve outcomes. In Mexico, for example, PPPs have long been a key tool to finance cultural infrastructure, with notable successes. A well-structured cultural PPP focuses on the whole life-cycle cost of a project, not just construction, which often leads to better design, quality, and sustainability than traditional public works. As the International Project Finance Association notes, PPP procurement tends to emphasize long-term performance: “when a PPP is negotiated it focuses on the whole life cost of the project, not simply on initial construction cost. It identifies the long-term cost and assesses the sustainability of the project.” In other words, PPPs align the interests of the private partner with the enduring success of the cultural asset, incentivizing efficient operations and maintenance over decades.

Another rationale is that PPPs diversify funding sources for culture. Traditional cultural funding relies heavily on government subsidies and philanthropy, which can be volatile. A PPP model allows revenue streams from private operations (ticket sales, rentals, sponsorships, etc.) to complement public funding. This “helpful mix of stability and flexibility” – blending public investment with private sponsorship and earned income – can sustain arts institutions through economic ups and downs. In summary, PPPs offer a strategic pathway for governments to deliver high-quality cultural facilities without shouldering the full financial load, while introducing private-sector efficiencies and innovation.

The Revenue Challenge in Cultural Projects

Despite their public value, cultural institutions face unique challenges in generating revenue and achieving cost recovery. Unlike infrastructure that naturally yields user fees (tolls, utility bills, etc.), museums and cultural centers provide largely public goods – education, community identity, creative inspiration – that are hard to monetize fully. Admission tickets and gift shop sales rarely cover operating costs for museums or art centers. Many cultural PPP projects thus confront long payback periods and uncertain income, which can deter private investors if not mitigated. Studies have found that museum PPP projects in particular “are particularly vulnerable to investment uncertainty, construction difficulties, high communication and cooperation costs, as well as long revenue cycles.” In other words, the financial returns in cultural projects often materialize slowly (if at all), making them riskier ventures for private partners relative to commercial projects.

Several factors contribute to this revenue challenge. First, cultural institutions prioritize public access and education, so ticket prices are often kept affordable (or free) due to social mission, limiting income. Second, attendance can be unpredictable and subject to seasonality or trends, affecting revenue stability. Third, cultural assets usually have high fixed costs – specialized staff, climate-controlled facilities, continuous programming – that don’t shrink easily when income dips. These dynamics can lead to chronic operating deficits if the business model isn’t carefully designed. Indeed, in China’s museum sector for instance, it is estimated that nearly 90% of museum revenues come from government subsidies, with only ~4% from “social” (earned) income – illustrating the gap that must be filled by either public support or creative revenue generation.

Another challenge is creating the right incentives for private participation. In the cultural sector, legal and policy frameworks haven’t always encouraged private investment. Researchers note that “a lack of alignment between the relevant laws, regulations, and policies” in cultural heritage sectors can result in “no apparent incentive effect” for private partners. In other words, if there are no tax breaks, property rights, or revenue-sharing mechanisms that allow a reasonable return, private entities will shy away. Similarly, cultural PPPs often face stakeholder complexities – multiple government bodies, local communities, donors, artists – which can lead to conflicting objectives. Managing these relationships entails high transaction and coordination costs.

Finally, experience shows that without careful risk allocation, cultural PPPs can fail or face renegotiation. Globally, the failure rate of PPP projects in the public cultural sector has been high, underscoring the need for robust risk mitigation. To attract and retain private partners, governments often must offer guarantees or support. For instance, successful cultural PPPs have included mechanisms like minimum revenue guarantees, public operational subsidies, or upfront grants to make projects bankable. In summary, the inherent revenue weakness of many cultural projects demands innovative financial structuring in PPPs – otherwise the risk of structural deficits simply shifts to the private partner, jeopardizing project sustainability.

Innovative Mechanisms for Financial Sustainability

To make cultural PPPs viable and avoid structural deficits, project designers around the world are employing creative revenue-generation and cost-recovery mechanisms. These go beyond basic ticket sales and aim to leverage the full economic potential of cultural assets:

Dynamic Ticketing Systems: Cultural venues are increasingly using smart ticketing strategies to maximize attendance and income. For example, dynamic pricing of museum admission can charge higher prices during peak demand and offer discounts in off-peak times, optimizing revenue without compromising access. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) experimented with raising prices by a few dollars during a blockbuster exhibition’s final weeks and saw increased revenue with no visitor complaints. By using data-driven pricing and timed ticketing, museums and attractions can increase yield per visitor while smoothing crowd patterns, thus improving both financial and visitor experience outcomes. Modern ticketing software also facilitates online sales, bundling of special exhibits or tours, and membership conversion, all of which can bolster revenue.

Venue Rentals and Commercial Uses: Many cultural centers are monetizing their spaces through rentals for events, retail, and hospitality. Museums often have architecturally striking halls, theaters, or gardens that can host private events (weddings, corporate functions, film shoots) for a fee. These rentals tap into “a lucrative market, generating revenue from a non-traditional source”. For instance, museums like the Smithsonian Institution have long rented out galleries after hours for events, bringing in substantial income. Similarly, incorporating commercial outlets on-site – cafés, restaurants, bookstores, artisan shops – can provide steady lease revenue. A well-curated restaurant or shop not only earns rent but also enhances the visitor experience. In creative industry hubs or arts districts, leasing studio or office space to creative businesses (design firms, production companies) is another strategy. By having an anchor tenant or mix of tenants, the project secures predictable rental income. In one development plan, the government even considered taking space as an anchor tenant itself – signing a long-term lease in a private mixed-use project – to help amortize construction costs and guarantee occupancy. This kind of anchor tenancy can reduce risk for the developer and ensure the cultural facility’s costs are partly covered by lease payments.

Digital Content Monetization: Embracing digital channels allows cultural institutions to transcend physical footfall. Museums have begun offering paid virtual access to their content – for example, exclusive online exhibits, virtual reality tours of gallery highlights, or livestreamed performances and lectures behind a paywall. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this trend, with many museums hosting ticketed virtual tours and workshops for global audiences. Such digital initiatives create new revenue with relatively low marginal cost, leveraging existing collections and expertise. Additionally, museums are monetizing their intellectual property (IP) through licensing. Art museums can license high-quality images of their collections for use in books, films, or merchandise. As one example, the Guggenheim Museum uses a dedicated agent (360° Enterprise) to manage worldwide licensing of its brand and collection images. In France, a centralized agency (Réunion des Musées Nationaux) handles IP rights for dozens of state museums, effectively turning cultural content into a revenue stream through royalties. Likewise, performing arts centers and audiovisual hubs can license recordings, develop subscription streaming services for performances, or partner with platforms (like a Netflix partnership for local film content) to generate income beyond the venue’s walls.

Public-Private Blends and Endowments: Some innovative models blend public, private, and philanthropic funding in structured ways. Cultural PPPs can establish endowment funds or trusts that draw initial capital from government and private donors, then invest it to provide a steady income for operations. The Nebraska Cultural Endowment in the U.S. is one example: it was created by state legislation to support arts across the state, with every private donation matched dollar-for-dollar by the State of Nebraska. This matching mechanism doubled the impact of private gifts and built a corpus of $30 million, generating about $1 million annually for cultural grants. Such trust funds can be part of a PPP, where the public sector provides seed funding or matching incentives to unlock private philanthropy at scale. Another strategy is “replace taxes with in-kind payments” policies: France allows individuals or firms to donate art or cultural assets in lieu of certain taxes, enriching public collections while giving the donor tax relief. This approach, which helped establish the Picasso Museum in Paris, effectively treats cultural value as a form of payment, benefiting both public heritage and private contributors.

Anchor Tenants and Mixed-Use Development: Embedding cultural facilities within larger real estate developments can also bolster financial viability. For instance, a new museum or cultural center might occupy part of a commercial development as an anchor attraction that draws foot traffic to the area. The developer, in turn, can cross-subsidize the cultural space through profits from offices, residences, or retail in the complex. In practice, a public facility lease as an anchor tenant can be the linchpin for project financing, providing the guaranteed long-term lease needed to underwrite a mixed-use project. One case study from Virginia (USA) showed that identifying a planned cultural center as the anchor tenant helped the private owner secure financing, with a lease long enough to repay construction costs. Similarly, cultural districts often flourish when a major institution (e.g. a national theater or gallery) anchors the area, surrounded by private businesses that benefit from and support the cultural footfall. This symbiosis is a form of PPP at the district level: the public invests in the cultural magnet, and the private sector invests in complementary commercial facilities, each reinforcing the other’s success.

In combination, these mechanisms aim to build a diverse revenue portfolio for cultural PPP projects. Instead of relying solely on one source (like government subsidy or basic tickets), successful models tap into multiple streams – visitor admissions, events, rentals, digital audiences, merchandising, donations, and more. The goal is not to commercialize culture for profit’s sake, but to ensure that cultural centers have enough income to thrive and fulfill their public mission without running deficits. Innovative revenue strategies, coupled with prudent cost management (e.g. energy-efficient design to lower operating costs, shared services among multiple venues), can significantly improve the financial sustainability of cultural infrastructure.

International PPP Models in Culture: Success Stories

Around the world, a variety of PPP approaches have been trialed in the cultural sector – some yielding impressive results. Success requires tailoring the PPP structure to the cultural context, balancing profit motives with cultural objectives. Here we highlight a few international examples from different regions:

Gran Museo del Mundo Maya (Mérida, Mexico): A flagship cultural PPP in Latin America, this world-class museum in Yucatán was developed via a 20-year PPP concession. Opened in 2012–2013, the Gran Museo del Mundo Maya celebrates Mayan heritage in a region where tourism is vital. The state government lacked the funds to build a modern museum on its own, so it partnered with a private developer (Grupo Hermes) and multilateral financiers. Grupo Hermes invested roughly $58.3 million in the project and in return won the right to build and operate the museum for 20 years. The Inter-American Investment Corporation (private arm of IDB) also provided a $7.4 million loan for outfitting exhibits and maintenance. This PPP structure meant the private partner carried the upfront cost and assumed operational responsibilities, while the government provided oversight and a revenue framework (likely including a mix of ticket sales, subsidies, and ancillary income to recoup the investment). The results have been remarkable: the museum is “already a hit”, drawing tourists from across Mexico and abroad, and has been called “the greatest cultural asset of the century” for the region.

By focusing on quality and long-term sustainability, the PPP delivered a museum “to a high standard and quality” that the local government alone could not have achieved. The Gran Museo’s success also illustrates alignment with tourism strategy – Yucatán has financed its tourism infrastructure projects exclusively via PPPs since 2011, recognizing that cultural attractions fuel the tourism economy. Importantly, this PPP was structured to avoid deficits: Grupo Hermes as operator has an incentive to maximize revenue (through visitors and events) and manage costs efficiently, while the government likely provides agreed payments or profit-sharing to ensure viability. The museum created thousands of jobs during construction and operation, and stands as both a cultural milestone and an economic asset for the region. Its PPP template is now being looked at for other cultural projects in Mexico.

The High Line (New York City, USA): While not a museum, the High Line is a renowned public park and cultural space that exemplifies a successful public-private partnership in the arts and urban regeneration. The High Line park – built on an old elevated railway – is owned by the City of New York but was designed, financed, and is nearly 100% operated by a private nonprofit (Friends of the High Line) in partnership with the city. Public seed funding (over $130 million from city, state, and federal sources) helped launch the project, but private donations (from philanthropists, foundations, and corporations) cover the bulk of its annual operating budget. This model leverages private philanthropy and business support to maintain a public cultural space, relieving the city of financial burden. The High Line’s innovative contributions – from rezoning efforts that allowed value capture, to corporate-sponsored features like the “Coach Passage” through a company’s HQ – show how creative risk-sharing can work. The city retained ownership and provided regulatory support (like zoning changes to spur nearby development), while the private partner ensured design excellence and community programming. Today, the High Line’s success is evident in the millions of visitors it attracts and the transformation of the surrounding neighborhood. It illustrates how a PPP can prevent deficits by shifting operating costs to a privately run conservancy model fueled by diverse revenue: donations (including “membership” programs for supporters), concessions, and events.

Pittsburgh Cultural District (USA): Another example of partnership-driven cultural development is the Pittsburgh Cultural District. In the 1980s, downtown Pittsburgh’s seedy urban area was revitalized through a collaboration led by the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, a nonprofit that marshaled both public and private backing. Over decades, this partnership transformed a 14-block district, renovating historic theaters, building galleries and public art spaces, and seeding cafes and businesses. The city and state provided capital funds and supportive policies, while private foundations, corporations, and individual donors contributed substantially to acquisition and programming. Today the Cultural District draws over 2 million visitors a year, hosts 1,500 events, and generates an estimated $303 million in economic impact. It’s cited as “a great example that highlights the versatility of PPPs” in the arts, showing that “cross-sector investment and long-term collaboration” can revitalize urban areas at scale. The operational funding of the district comes from a blend of earned income (ticket sales, venue rentals), real estate revenues, and ongoing fundraising. By sharing risks and rewards across sectors, Pittsburgh avoided saddling taxpayers alone with the costs of running multiple venues; instead the value created (higher land values, more business activity) feeds back through private leases and city tax base. This model aligns closely with urban development strategies – treating cultural amenities as catalysts for economic growth and downtown livability.

European Heritage PPPs: In Europe, where cultural heritage is abundant, PPPs have been used to restore and operate historic sites. Models include long-term leases of heritage buildings to private operators who turn them into museums or cultural centers with mixed commercial use. An example is the Taiwan Museum of Marine Biology & Aquarium, often cited as a pioneering PPP in the museum field (though in Asia). Opened in 2000, it was one of the first cases where a public museum’s operations (exhibitions and public spaces) were outsourced to a private company under a Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) arrangement. The government retained ownership but received a fixed royalty and a share of operating profits from the private operator. This model ensured the museum would not run at a loss for the government; the private partner had to run it efficiently to recoup their investment, and the public sector benefited through revenue share. Other European innovations include national governments providing tax incentives for cultural patronage (for instance, the UK’s Gift Aid scheme treats museum donations as tax-deductible and even refunds a portion to the museum, encouraging more giving). France’s practice of accepting art in lieu of inheritance tax, as mentioned, also enriched public collections at moderate public cost. While these are not PPPs in the conventional sense of infrastructure deals, they are part of the public-private cooperation toolkit that keeps cultural institutions funded and open.

Audiovisual and Creative Industry Hubs: PPPs are also emerging in the audiovisual sector, where building studios and creative incubators can be capital-intensive. For instance, some countries have developed “film cities” or media parks through PPP frameworks. A notable concept is to integrate film production facilities with public attractions to bolster revenues. In India, proposals for a Film City PPP include not just soundstages and backlots for filmmakers, but also theme parks, museums, and tours for tourists. The idea is that tourism and leisure components cross-subsidize the production infrastructure: visitors pay for theme park rides, set visits, and film museum tickets, providing cash flow that supports the viability of the studios. Dubai Studio City similarly blends commercial office space for media companies with community and educational facilities to create a hub that is financially sustainable (tenants’ rent funds the infrastructure). These creative hubs often rely on anchor tenants (like a national broadcaster or an international studio) whose long-term leases justify the investment. The government’s role might be providing land or tax-free zones, while private developers build and manage the facilities, earning returns from both industry clients and visitors. The Rwanda Creative Industries Program design (2024) provides another example: it explicitly proposed developing creative hubs and studios “through PPPs” – recognizing that private co-investment is vital to get infrastructure like multimedia centers off the ground. By structuring these hubs as PPPs, Rwanda aims to tap private media companies and investors to share costs and expertise, ensuring the centers don’t become drains on the public budget.

These cases illustrate that there is no one-size-fits-all PPP model for culture – the structures range from concessions and management contracts to nonprofit operating agreements and trust funds. What they share is a partnership ethos: leveraging the strengths of each sector. The public sector often provides initial support (capital grants, guarantees, policy incentives) and protects the public interest (access, preservation), while the private or third sector partner brings efficiency, innovation, and additional resources. When done well, cultural PPPs can deliver world-class facilities without endemic deficits, as revenues and responsibilities are shared. Success also depends on intangibles: trust between sectors, political will, and community support (cultural projects can be sensitive symbols of identity, requiring stakeholder buy-in). The pitfalls – such as disputes over mission vs. profit, or an operator walking away if returns falter – must be managed via careful contract design and relationship management.

Governance and Risk-Sharing to Prevent Deficits

A critical aspect of cultural PPPs is how governance and risk-sharing are arranged. The goal is to allocate risks to the party best able to manage them, and to create checks and balances so neither side exploits the other nor leaves the project under-resourced. Key governance considerations include:

Contract Structure: Many cultural PPPs use long-term concession contracts or leases, where a private entity is responsible for design, build, and operation for a defined period (e.g. 20–30 years), after which the facility may revert to public management. Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) and similar models (Build-Transfer-Operate, Rehabilitate-Operate-Transfer for historic buildings, etc.) are common. For example, a city might contract a private firm to build a new art museum and operate it for 30 years, maintaining service standards, in return for retention of all or part of the revenues plus possibly an “availability payment” from the government to cover any gap. Performance clauses are essential: the contract should specify maintenance standards, programming requirements (e.g. number of free community days), and preservation obligations for heritage sites. This ensures the private partner doesn’t cut corners to save money, which could undermine the cultural mission.

Public Oversight and Ownership: In most cases, the government retains ownership of the core cultural assets (the building, the collection if applicable) to safeguard public interest. A governing board or steering committee might be established with representatives from both the public and private sides – and often independent experts or community members – to oversee that both financial and cultural targets are met. For instance, many PPP-run museums still have a public sector representative or a trust that ensures the museum’s curatorial integrity is upheld even as the private operator runs day-to-day business. Transparency mechanisms, like regular reporting and audits, help detect if an operating deficit is looming so that corrective action can be taken jointly.

Risk Allocation: To avoid structural deficits, risks like construction overruns, low visitation, or cost inflation need to be apportioned clearly. Typically, the private partner takes construction risk (delivering the project on budget and on time) and operational risk (managing staffing, maintenance, and commercial activities efficiently). The public sector may take on demand risk in part, because cultural visitation can be uncertain. For example, the government might agree to a subsidy or minimum revenue guarantee if annual attendance falls below a threshold, so the private operator isn’t bankrupted by low turnout beyond their control. Conversely, revenue-sharing mechanisms can be set so that if the private operator does very well (high profits), a portion flows back to the public side – aligning incentives and preventing excessive commercialization. The academic literature suggests that a combination of “government guarantees, revenue guarantees, and risk compensation” may be needed in cultural PPP contracts to keep private partners committed. For instance, in Italy some heritage site PPPs include clauses where the state guarantees a baseline income to the operator, or in Spain a concession to run a cultural center may come with public operating grants for the first few years until the project stabilizes.

Flexible Compensation Models: Because one size doesn’t fit all, PPP agreements might embed flexible compensation schemes. Some innovative contracts treat government support as a “real option” – essentially an emergency backstop that can be invoked if certain adverse scenarios occur (like a major tourism downturn). Others have dynamic compensation models that adjust the private party’s fees based on performance metrics (e.g. higher payment or profit-share if they exceed visitor number targets, and lower if they don’t). By dynamically tuning incentives, these models aim to keep the partnership sustainable and fair over time. The private partner is motivated to maximize performance but also protected from extreme downside risk, which in turn protects the public interest by ensuring continuous service.

Nonprofit and Community Involvement: In cultural PPPs, sometimes the “private” partner is actually a nonprofit organization or a foundation rather than a for-profit company. This is the case in many U.S. examples (High Line, Cultural Trust, etc.) where a nonprofit manages the venue with a philanthropic mindset but using private-sector tools. Involving nonprofits or even community groups (the “Public-Private-People partnership (P4)” concept) can enhance governance by adding a layer of public accountability. For example, a community trust might hold the lease to a historic theater and hire a private firm to operate it, thus the community trust oversees that the operator meets local cultural needs. Such multi-party governance can prevent purely profit-driven decisions that might erode the cultural value, while still leveraging professional management.

In essence, the governance of cultural PPPs must balance financial rigor with cultural stewardship. The contract should clearly define who handles what costs and risks – from routine maintenance to insurance to content curation – to avoid ambiguity that could lead to cost overruns or service gaps. It is often advisable that governments conduct rigorous feasibility studies and value-for-money analysis before entering a cultural PPP, to determine what level of support is needed to make the project viable. If analysis shows that no realistic projection has the project breaking even, then the PPP should be structured with an upfront viability gap funding (a capital grant to cover the non-remunerative portion of construction) rather than burdening the operator with debt they cannot service. Likewise, maintenance-heavy assets (old heritage buildings) might be better suited to maintenance contracts with performance incentives, rather than full risk transfer.

Successful governance also means having an exit strategy: terms for handback or termination. For instance, at the end of the PPP term, the public sector should receive the asset back in good condition – so the contract might include a reserve fund that the operator must pay into for long-term renewals (preventing the scenario of a dilapidated facility returning to the state). If the operator fails (financially or in service quality), step-in rights allow the government to temporarily take over or re-tender the contract to a new operator, ensuring continuity for the public.

By designing governance and risk-sharing smartly, cultural PPPs can prevent the dreaded structural deficit. The guiding principle is to anticipate the financial weak points (low revenue periods, high fixed costs, conservation expenses) and arrange support for those, while still pushing the private side to be as efficient and entrepreneurial as possible. With clear rules and mutual commitment, PPPs can keep cultural institutions both financially afloat and true to their mission.

Integrating Culture PPPs with Urban Development and Tourism

Cultural PPP projects do not exist in a vacuum – they are often linchpins in broader urban and regional development plans. Aligning a cultural PPP with city development and tourism strategies can greatly enhance its success and sustainability. There are several dimensions to this alignment:

Urban Regeneration: Large cultural investments are frequently used as catalysts to revive downtowns or neglected neighborhoods (the so-called “Bilbao effect”, named after the Guggenheim Bilbao museum’s impact). A museum or arts center PPP can anchor a redevelopment zone, attracting private real estate investment in hotels, restaurants, and creative industries around it. This was the case in Pittsburgh’s Cultural District as discussed, and also in smaller examples like the creation of arts hubs in disinvested city blocks. When a PPP cultural project is part of an urban regeneration masterplan, the city can leverage tools like value capture – increased property tax revenues from rising land values – to support the project financially. For example, New York City’s rezoning around the High Line allowed developers to build higher in exchange for contributions, indirectly funding the park’s upkeep. In PPP terms, a city might contribute land or zoning incentives as its share in the partnership, confident that the cultural anchor will spur enough economic uplift to justify it. Integrating with urban development also means planning transport, signage, and public spaces to ensure the cultural site is accessible and woven into the city’s fabric, enhancing usage and revenue.

Tourism and Destination Marketing: Cultural attractions are major draws for tourism, and tourism in turn is a source of revenue for those attractions (through ticket sales and ancillary spending). A PPP cultural project that syncs with a region’s tourism strategy can tap into marketing campaigns, tour operator partnerships, and visitor infrastructure. For instance, the Gran Museo del Mundo Maya was explicitly part of Yucatán’s strategy to bolster cultural tourism – Yucatán being a “tourism epicentre” due to Mayan heritage. The museum’s inclusion in travel itineraries and promotion by tourism boards drives higher attendance, benefiting the PPP’s bottom line. Governments can support PPP cultural projects by bundling them in tourism passes (e.g. city passes that give entry to multiple attractions) or by situating visitor centers and info hubs at these sites. In return, a well-run cultural PPP enhances the destination’s appeal, increasing overall tourist stays and spending. Integration with tourism infrastructure is also key: as seen in film city concepts, adding components like hotels, restaurants, and entertainment around a cultural hub can open additional revenue. A KPMG analysis noted that building hotels, retail, and recreation alongside a film studio hub “opens other sources of revenue generation in addition to studio leasing” and boosts competitiveness as a destination. In practice, PPP contracts might even allow the private partner to develop some commercial real estate on-site (e.g. a museum complex that includes a pay-parking garage, cafes, and a boutique hotel) to cross-subsidize the cultural facility.

Community and Social Development: Aligning with local development goals ensures community buy-in, which is crucial for cultural projects. A PPP that contributes to social outcomes – for example, a creative center offering youth training, or a museum providing educational outreach to schools – can justify public investment beyond pure economics. Such alignment might unlock additional funding streams, like development bank grants or social impact bonds, to support the PPP. Moreover, when local communities see tangible benefits (jobs, improved public space, cultural pride), they are more likely to support ticket prices or local tax measures that help sustain the venue. A cultural PPP can also partner with nearby educational institutions (universities, art schools), acting as an incubator for talent and innovation in the area. All these ties root the project in the city’s broader development narrative, making it less isolated financially.

Branding and Cultural Identity: Cities increasingly brand themselves around culture – consider Edinburgh as a festival city, or Medellín, Colombia positioning as a hub of urban art and tech creativity. A PPP project can serve as the iconic embodiment of that brand. When city leadership incorporates the cultural PPP into its international marketing (conferences, tourism expos, investment forums), it can attract sponsors and donors to the project by highlighting prestige and impact. For instance, a city that brands as a “creative city” might attract a multinational tech sponsor for its new media arts center PPP, seeing alignment in values. The PPP benefits from these sponsorships financially and through increased visitation.

Cluster Development: Particularly for audiovisual hubs and creative centers, aligning with economic development means fostering clusters. A PPP that builds a film studio, for example, should ideally be part of a broader plan to grow the film industry cluster – including incentives for production companies, film festivals, training programs, etc. This cluster approach, often supported by government policy (tax credits for film production, grants for startups in creative industries), will feed business to the PPP facility (studios get rented, talent stays local) ensuring its utilization and revenue. In Nigeria’s fast-growing film industry (Nollywood), one could imagine a PPP film village supported by government training schemes and international partnerships that guarantee a pipeline of productions. Aninver’s work in Africa suggests that creative industries can flourish with “targeted interventions” like connecting creatives to financing and markets – a creative hub PPP could be the physical locus of those interventions, housing co-working spaces, studios, and a marketplace for creative goods. Alignment with such programs means the hub won’t sit empty; it will be buzzing with supported activity.

In summary, when cultural PPPs are conceived not just as standalone projects but as integral pieces of urban and economic development, they tap into synergies that improve their financial outlook. The footfall from tourism, the support from city budgets (justified by regeneration returns), and the engagement of stakeholders from other sectors all help avoid deficits. The Pittsburgh Cultural District’s economic impact, the Bilbao Guggenheim’s tourism windfall, or the revitalization of a city like Málaga (Spain) with a “museum mile” are proof that culture-led development can yield dividends. The PPP format in these contexts is a means to an end – ensuring that the cultural infrastructure can be built and maintained in a way that the rising tide of urban prosperity lifts it along.

Aninver’s Experience with Cultural PPPs

Aninver Development Partners has been at the forefront of advising on creative economy and infrastructure projects in emerging markets, including initiatives that involve cultural PPP components. Drawing on its global consulting experience, Aninver has contributed to the planning and design of financially sustainable cultural and creative facilities in regions like Latin America and Africa. A few pertinent examples include:

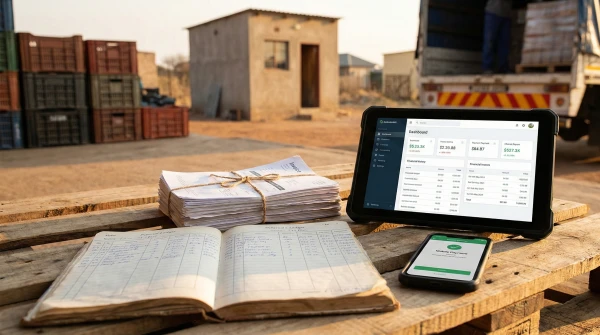

Creative Industry Hubs in Africa: In Rwanda, Aninver assisted the government (with African Development Bank support) in designing a National Creative Industries Program (2024–2025) that explicitly incorporated PPP strategies. The program feasibility study recommended developing new creative hubs – such as multimedia production centers, arts venues, and co-working spaces for artists – through public-private partnerships. By bringing in private co-investors or operators for these hubs, Rwanda aims to ensure the infrastructure can be funded and managed sustainably rather than relying solely on government budgets. Aninver’s work involved mapping existing creative spaces and assessing needs for PPP development, crafting a plan where government would facilitate and possibly co-finance hubs while private entities would invest capital or expertise. This approach reduces the risk of future deficits by involving entrepreneurs who will run the hubs with business discipline, attracting paying users (e.g. film producers renting studio time or designers leasing studios) to cover operating costs. Similarly, in Sierra Leone, Aninver conducted a Creative Economy Diagnostic (2025) which highlighted the need for creative spaces/infrastructure and private sector engagement in arts and culture. The study’s recommendations included exploring PPP or community-based models to open venues for music, film, and art in a country where public funding is scarce. By identifying how social forces and private investors can be incentivized to participate (through grants, matching funds, or tax incentives), Aninver helped set the stage for sustainable cultural projects that won’t rely 100% on government subvention.

Tourism and Cultural Heritage Projects: Aninver has also worked on projects tying culture with tourism development, advising on strategies that often involve PPP elements. For example, in Malawi Aninver developed an Ecotourism Strategy (2019) aimed at preserving natural and cultural heritage while promoting investment. The strategy provided guidance on product development – including cultural heritage sites and community museums – and on involving local communities and private investors in conservation and visitor services. While not a single PPP project, this kind of work lays the groundwork for future PPPs (such as private lodge concessions in heritage sites or joint management of cultural villages). By emphasizing infrastructure development and community participation alongside preservation of cultural heritage, Aninver’s plan aligns public and private interests. In practice, this could mean, for instance, a PPP to upgrade a cultural village with a private tour operator who manages it, or a museum in a national park co-run by the parks agency and a private company, ensuring the site generates enough revenue from eco-tourism to be self-sustaining. Aninver has similarly contributed to tourism master plans and investment promotion in other countries (e.g. a strategic roadmap for tourism in Barbados, projects in Rwanda’s Kibuye region, and others), always with an eye on how collaborations between the public sector and private investors can bring capital and efficiency to cultural and hospitality assets.

Research and Knowledge Sharing in PPPs: Beyond direct project design, Aninver has been involved in knowledge initiatives that include cultural sectors. For instance, Aninver executed PPP research in Latin America (for clients like the Inter-American Development Bank and others) to identify opportunities across various sectors. While that particular 2016–17 research focused on energy and telecom sectors, Aninver’s broader advisory portfolio includes supporting institutions in developing PPP frameworks that can apply to social sectors too. In engagements with multilateral development banks, Aninver has contributed to the discourse on how to adapt PPP models for “softer” sectors like culture and education, recognizing that viability often requires blending public support with innovative revenue models (much of what has been discussed in this article). By sharing best practices and lessons learned, Aninver helps governments in Latin America and Africa structure PPP contracts that incorporate proper risk-sharing and incentive mechanisms, whether for a museum, a convention center, or a technology park. For example, the firm’s insights on matching grants or on tax incentives to encourage private investment in culture echo the global examples cited above (like matching funds in Nebraska or tax swaps in France), but tailored to developing country contexts where attracting private capital to culture can be challenging.

Project Implementation Support: When PPP projects move to implementation, Aninver’s on-ground support in various countries indirectly benefits cultural components. A case in point: in a Promoting Investment and Competitiveness project for the tourism sector in The Gambia or Malawi, Aninver’s role in improving the business environment and highlighting cultural tourism assets paves the way for PPPs. For instance, simplifying how a private operator could lease a historic fort or an island cultural site can trigger a PPP proposal. In their work in Panama, for example (with IDB and IDIAP, though focused on agricultural innovation), the methodologies developed for inclusive public-private collaboration could be analogous to cultural industries promotion. Additionally, Aninver’s involvement in “Blue Economy” strategies (Barbados, Trinidad & Tobago) often touches on coastal heritage and cultural tourism – which might include plans for PPP-managed marine museums or heritage centers as part of sustainable tourism.

In all these efforts, a unifying theme is ensuring no structural deficit in the long run: projects are conceived with sustainability in mind, building in revenue generation or private sector efficiency to cover costs. Aninver’s multi-sector expertise (spanning infrastructure, creative industries, tourism, etc.) positions it to find cross-cutting solutions – for example, using a tourism PPP approach (like concessioning a facility) for a cultural site, or leveraging creative industry growth trends to justify private investment. By advising on everything from feasibility studies to governance frameworks, Aninver has helped clients in Latin America and Africa move towards cultural PPP models that aim to be financially self-sustaining while delivering social value.