Our Views

How to Prepare a Complete Feasibility Study for a PPP Project

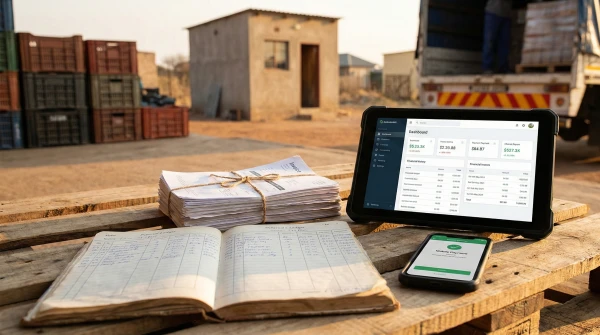

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) can be powerful tools to deliver infrastructure and public services – from hospitals and roads to water systems and logistics corridors. But no PPP structure, no matter how clever, can fix a weak project. If the feasibility study is rushed, incomplete or overly optimistic, the problems aparecen después: licitaciones fallidas, renegociaciones, presión fiscal inesperada o, lo más grave, servicios deficientes para la ciudadanía.

A good PPP feasibility study does the opposite: it reduces uncertainty, tests alternatives, and gives governments, financiers and operators a shared, realistic picture of what the project can deliver and under what conditions. At Aninver, we’ve been involved in PPP-related assignments in healthcare, transport, energy, water and blue economy – from reviewing the business case of a hospital PPP in Spain, to researching PPP opportunities in Latin America’s energy and telecoms sectors, to stress-testing the feasibility of complex infrastructure such as the Meta River navigability corridor in Colombia. Across these experiences, the logic of a solid feasibility study is surprisingly similar.

1. Start with the problem, not the PPP

A complete feasibility study begins with a deceptively simple question: what problem are we trying to solve?

Before talking about risk allocation or payment mechanisms, the study needs to clarify the service gap, who is affected and what public policy objectives are at stake. Is there a lack of hospital capacity in a fast-growing area? Is a congested road corridor limiting trade? Are secondary cities suffering from unreliable water service?

In our review of a health PPP project in southern Spain, the first task was not financial modelling, but checking whether the proposed hospital size, catchment area and service mix actually responded to demographic trends and healthcare needs. Only when the “why” was solid did the PPP discussion make sense. A good feasibility study leaves this problem definition clearly documented so that a minister, a banker or a citizen can understand why the project exists.

2. Understand demand and stakeholders in depth

Once the problem is defined, the next step is to understand who will use the service and who is affected by the project. This goes much further than a basic traffic count or a simple ratio of beds per inhabitant.

For a transport PPP, this might involve origin–destination surveys, talking to logistics operators and analysing competing routes or modes. For a hospital PPP, it means looking at patient flows, the role of existing public and private providers, referral patterns, and waiting times.

In parallel, the study should build a clear picture of the institutional and social landscape: which authorities regulate the sector, who owns the land, which communities live in the area, where potential political or social risks may arise. In our work mapping PPP opportunities in Mexico, Peru, Chile, Colombia and Panama, we often found technically attractive ideas that were not viable because a key regulator was unconvinced, a municipality feared expropriations, or line ministries had overlapping mandates. A robust feasibility study anticipates these tensions instead of discovering them too late.

3. Compare technical options instead of locking into one

A PPP feasibility study should not simply validate a single pre-defined solution. Its real value lies in testing alternatives and explaining why one option makes more sense than the others in terms of cost, risk and long-term impact. Even when the project seems “obvious” from an engineering point of view, there are always different ways to structure, phase and manage it.

In airport projects such as the Armenia Airport PPP in Colombia, this becomes very clear. Beyond the physical works, key decisions relate to how the future operator will be organised, how insurance risks will be shared, and how tax obligations will affect long-term cash flows. During the feasibility analysis, different configurations can be compared: more centralized or more lean operator models, alternative insurance packages with different deductibles and coverage levels, or fiscal structures that shift how CAPEX and OPEX are treated over time. Each option changes the project’s risk profile, bankability and attractiveness for investors.

By systematically comparing these alternatives, the feasibility study helps reveal which structure is truly sustainable – not just technically, but financially and institutionally. It shows, for example, how a certain insurance scheme may reduce lender risk but increase annual costs, or how a particular organisational setup may strengthen accountability but require more upfront capacity building.

The goal is not to produce full construction drawings or a final legal contract, but to reach a level of technical and operational definition that makes the numbers and risks credible: CAPEX, OPEX, guarantee needs, contingent liabilities and resilience to shocks. A well-prepared feasibility study explains these choices and their implications in plain language, so public decision-makers, financiers and future operators all understand exactly what project they are backing.

4. Put the legal and institutional reality on the table

No project exists in a vacuum. A solid feasibility study must examine whether the legal and institutional framework supports the proposed PPP. It should clarify whether current legislation allows availability payments, user fees or guarantees; which entity has the mandate to sign the contract and commit long-term payments; how PPP, procurement, sector and environmental rules interact; and whether there are credible mechanisms for regulation and dispute resolution.

In some of our PPP-related work in Latin America, part of the job has been to identify contradictions between PPP laws and sector regulations that could scare off investors or complicate contract enforcement. The feasibility study does not need to become a legal textbook, but it should clearly flag any issues and propose a way forward, whether through legal amendments, special approvals or institutional arrangements such as dedicated project companies or units.

5. Build a financial and economic case that people can trust

Only when the problem, demand, technical options and legal context are clear does it make sense to dive into numbers. A complete feasibility study must show whether the project is financially viable for the private partner, fiscally affordable for the public side, and economically beneficial for society.

For the private partner, the study analyses whether expected revenues – whether from tariffs, availability payments or ancillary income – can cover investment, operations, maintenance, financing costs and a reasonable return, under different scenarios. For the government, it tests whether the payment obligations and potential contingent liabilities fit within realistic budget and debt limits. And for society as a whole, it examines whether time savings, better health outcomes, reduced emissions or lower user costs justify the investment when measured through cost–benefit analysis.

During our review of the hospital PPP in Spain, much of the work consisted of revisiting assumptions in the existing pre-feasibility study: demand projections, service mix, investment timing, and operating costs. Aligning the business model with realistic expectations was fundamental to deciding whether the project should move forward. A good feasibility study does not hide its assumptions in spreadsheets; it explains them in narrative form, showing clearly what drives the results.

6. Treat risk allocation as a design choice, not an appendix

Risk allocation is at the core of a PPP. A serious feasibility study doesn’t just add a risk matrix at the end; it uses risk as a design tool throughout the process. It identifies the main risks – construction, demand, regulatory, social and environmental, macroeconomic or technological – and discusses who is best placed to manage each one.

In complex initiatives such as the Meta River navigability PPP, some risks – for example, certain hydrological or environmental uncertainties – are extremely difficult for private partners to price. In these cases, the feasibility work needs to explore creative combinations of performance-based payments, phased investments or public co-financing, instead of pushing unmanageable exposure onto a concessionaire.

Ultimately, the study should help answer a simple question: does a PPP structure create more value than traditional public procurement, once risk is properly allocated and priced? If the answer is no, the PPP label adds little.

7. Listen to the market before freezing the design

One of the recurring weaknesses we have seen in PPP preparation is that market sounding happens too late. Advisors and governments may invest heavily in sophisticated modelling, but only speak to potential bidders when most design decisions are already locked in.

A complete feasibility process includes early and structured conversations with potential operators, financiers and local partners. These discussions are not about negotiating the contract in advance, but about checking whether the proposed risk allocation, payment mechanism and legal environment are genuinely bankable. Feedback can lead to adjustments in concession length, tariff indexation mechanisms, the treatment of land acquisition, or the level of government support needed.

Good feasibility studies document this market feedback and show how it has been incorporated, increasing confidence among potential bidders and financiers.

8. Finish with a roadmap, not just a recommendation

A feasibility study that ends with “the project is viable and should proceed as a PPP” is incomplete. Decision-makers need to know what happens next.

This means outlining the approvals required, additional studies to be prepared (detailed engineering, environmental and social assessments, resettlement plans), the steps for drafting bidding documents and contracts, the institutional set-up for project management, and a realistic timeline from now to financial close.

In our PPP-related work with governments and DFIs, this implementation roadmap is often one of the most practical outputs: it translates hundreds of pages of analysis into a clear sequence of actions, responsibilities and milestones.

What our experience has taught us

Working across sectors and regions, a few lessons come up again and again. Over-optimism is expensive: if demand is overstated or costs understated, the problem will surface sooner or later, often during procurement or early operations. Sector context matters: a hospital PPP, a river corridor and a digital programme share some PPP logic but differ radically in regulation, politics and social impact. Process is as important as product: building consensus, managing expectations and coordinating institutions are not “soft” tasks, but central pillars of a successful PPP. Above all, clarity beats complexity. The best feasibility studies are those that non-specialists can read and understand – what is proposed, why, what it costs, who takes which risks and what value the project brings.

Want to explore PPP practice in real projects?

If you’d like to see how these principles play out on the ground, we invite you to explore some of our work: from the review of a hospital PPP pre-feasibility study in Spain, to our Feasibility Study: Tax and Insurance Analysis for Armenia Airport Project, Colombia, or our support to strategic, complex projects such as the Meta River navigability corridor.

These and other assignments reflect our belief that a rigorous, honest feasibility study is not a bureaucratic step – it is the foundation for PPP projects that work for governments, private partners and, above all, citizens.