Our Views

Agri-PPP Without the Buzzwords: When PPPs Make Sense for Irrigation, Cold Chains, and Markets

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) in agriculture are often hyped with jargon, but the core idea is simple: the public and private sectors team up to deliver projects that neither could do as well alone. In agriculture, PPPs can bring investment, efficiency, and innovation to infrastructure like irrigation systems, cold storage facilities, and markets. The key is knowing when a PPP truly adds value. Below we cut through the buzzwords and explain in plain language when PPPs make sense for irrigation, cold chains, and markets.

PPPs in Irrigation: Bringing Water and Efficiency to Farmers

Irrigation is the lifeblood of agriculture, especially in dry regions. But large irrigation networks are expensive to build and maintain, and many government-run systems underperform. In some countries, canal systems operate at only about 30% efficiency, leaving much room for improvement. This is where a PPP can make sense. The government can handle core assets like dams and water sources, while a private partner manages the distribution network to farms, maintains canals, and even handles water pricing and fee collection. By sharing responsibilities, the public side retains control of water resources and the private side brings in capital and management know-how to reduce waste and improve service.

A real-world example comes from Morocco. In the early 2000s, citrus farmers in the Guerdane region faced severe water shortages and sinking groundwater levels. The government and IFC structured the world’s first irrigation PPP there, inviting a private operator to co-finance and run a new irrigation network. The project installed efficient drip irrigation and tapped surface water from a dam 90 km away, backed by nearly $40 million in private investment. The results were remarkable: by 2009, farmers could irrigate 10,000 hectares reliably without draining their aquifers, and by 2017 citrus production was 82% higher than before the project. In short, this PPP brought sustainable water supply and improved yields for nearly 2,000 farms, all while creating local jobs. This success was possible because farmers grew high-value crops (citrus) and were willing to pay for reliable water, making the project financially viable. It shows that PPPs in irrigation make sense when there is a clear revenue stream (like water fees or sales boosts) and when private innovation (like modern drip systems) can significantly raise productivity.

Morocco’s Guerdane irrigation PPP introduced drip systems to revive 10,000 hectares of citrus orchards. It brought in private investment and helped farmers weather droughts while boosting yields dramatically.

However, not every irrigation project should be a PPP. If farmers cannot afford water tariffs or if the scheme is very small, private investors may shy away. PPPs work best in irrigation when the scale is large enough and farmers’ income gains justify the costs. Governments can sweeten the deal by offering support like partial financing or guarantees, ensuring the project is bankable while keeping water affordable for farmers. The bottom line: PPPs make sense in irrigation when improved efficiency and reliability generate real value – higher crop yields, water savings, and farmer incomes – that can be used to pay back the investment.

PPPs in Cold Chains: Reducing Food Loss from Farm to Market

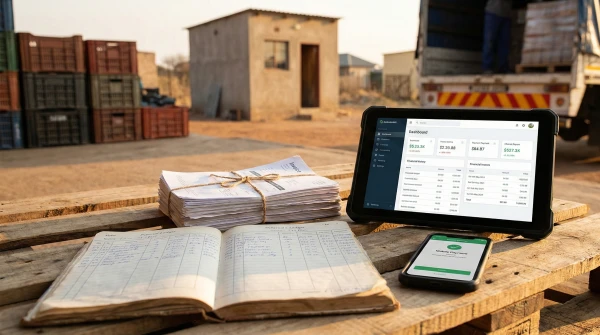

A cold chain refers to refrigerated storage and transportation that keeps food fresh from farm to fork. In many developing regions, the lack of cold storage and good warehouses leads to massive post-harvest losses – gluts of crops can rot when there’s nowhere to store them. For example, high production seasons often see prices crash and food spoilage increase, hurting farmers’ incomes. Building modern warehouses and cold storage facilities would help stabilize prices and reduce waste by preserving produce for longer. This is an area where PPPs can play a pivotal role.

Why PPP? Because governments may not have the funds or expertise to build and run hundreds of cold storage units, but private agribusinesses see an opportunity in food processing, storage, and distribution. A PPP can align these interests: the public side might provide land or capital subsidies, and the private partner invests in constructing and operating the facilities. One analysis notes that developing warehouse and cold storage infrastructure offers enormous opportunity for PPP, especially if public entities help overcome obstacles like land availability and small initial profit margins. In India, for instance, policy experts have suggested leasing public land (such as unused government or community land) to private investors on long-term contracts to encourage them to build cold stores and silos. This reduces the upfront burden on the private side and ensures the facilities are built where they are most needed.

In practice, we have seen steps in this direction. In Ghana, a World Bank-supported program looked at PPPs to expand grain storage in the northern Savannah region, where lack of warehouses was a bottleneck for farmers. The project’s goal was to rehabilitate old government silos and construct new warehouses through PPP and matching grants. By involving private operators, the plan was to create a financially sustainable model to maintain these storage sites and even operate them profitably (for example by charging storage fees or operating commodity trading services). Such a PPP approach can make sense when the private sector’s efficiency and market knowledge help ensure the storages are well-utilized and maintained, while public support keeps the costs reasonable for farmers.

That said, cold chain PPPs must be carefully structured because standalone cold warehouses in rural areas might not turn a profit immediately. Often, they need to be part of a bigger value chain – for example, integrated “food parks” or processing hubs where multiple businesses use the facilities. Governments can also offer viability gap funding (a one-time grant) to make projects attractive. When done right, PPPs in cold chains can significantly cut food losses and extend the market reach of farmers’ produce, all while introducing modern technology (like solar-powered cold rooms or efficient refrigeration) that purely public projects might not deploy.

PPPs in Markets: Modernizing How Farmers Sell

Rural and wholesale markets are where farmers and traders come together – but in many countries, these markets are outdated or informal. You might find a patch of land with makeshift stalls, no roof, no storage, and poor sanitation. Such conditions limit how much farmers earn and can even be health hazards. Building modern, covered markets with proper stalls, storage, electricity, and water can transform the trading experience for both sellers and buyers. The challenge is funding and managing these facilities long-term – a clear opportunity for a PPP if structured well.

In countries like India, experts observed that very few new agricultural markets were built in recent decades, and existing ones are fragmented and inefficient. They suggested that wholesale markets could be developed under PPP models similar to highways, using build-operate-transfer contracts with government support for viability. In simpler terms, a private developer could finance and construct a market, operate it for a number of years (earning through stall rentals, parking fees, etc.), and then hand it back to the government. The government might chip in with land or partial funding to ensure the project is attractive to investors. This approach leverages private sector efficiency in construction and management, while the public ensures the market serves local needs.

We can see this idea being applied in practice in parts of Africa. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) recently helped design PPP projects for new markets in Cotonou, Benin and Lomé, Togo. In those cities, many traders were selling in open-air bazaars with no shelter or facilities. The governments, with IFC’s help, decided to develop modern covered markets through a PPP scheme. Aninver (a consultancy) was hired to figure out the best PPP structure to attract qualified private partners and ensure the markets would be financially viable. This involved studying successful market cases, assessing demand (how many vendors and customers would use it), and determining revenue streams (like stall fees or shop rentals). Essentially, the private partner would invest in building the facility and then recover costs by operating the market efficiently – keeping it clean, secure, and well-organized – which in turn draws more business.

Even more directly tied to agriculture, Malawi is planning PPPs for cross-border markets that serve farmers and small traders. Many border trading posts in Malawi currently lack basic infrastructure (no proper sheds, storage, or services) and operate informally. Under a new EU-funded project, consultants are evaluating PPP options to build and run modern markets at key border points. The idea is that a private partner can bring in investment to construct marketplaces with facilities like warehouses, sanitation, and security, and then manage them to keep quality high. By doing so, the markets would better support regional trade and improve the livelihoods of small-scale traders (many of whom are women) who will benefit from safer, more accessible trading venues. The government’s goal in structuring these as PPPs is to ensure quality infrastructure and professional management, with the private sector taking on day-to-day operations while the public sector oversees to protect community interests. If successful, these PPP markets could reduce post-harvest losses (by providing storage), increase farmers’ earnings (by connecting them to more buyers), and boost regional commerce.

In summary, PPPs make sense for market infrastructure when the upgrade to a modern facility will generate revenue – through stall rentals, tourist visits, or increased volumes of trade – that a private operator can capture, and when the community gains a better marketplace without the government bearing the full cost. It’s a win-win: farmers and traders get a clean, well-managed place to do business, and the private investor earns a return over time through market fees.

Making PPPs Work: Focus on Value and Impact (Aninver’s Experience)

Across irrigation, cold chains, and markets, PPPs are not a silver bullet but a tool. They make the most sense when a project can realistically generate cash flow (from user fees, increased sales, or cost savings) and when private-sector innovation can significantly improve outcomes. PPPs should not be pursued for buzz or trendiness, but for clear value-for-money reasons: better services, faster implementation, or life-cycle cost savings compared to public delivery.

This practical approach is reflected in real projects that firms like Aninver have supported around the world. For example, Aninver’s teams have helped design PPP solutions for grain silos in Ghana, market infrastructure in West and Southern Africa, and irrigation feasibility studies – always with an eye on whether the PPP model adds value. In Malawi’s case, as noted, PPPs are being explored to deliver border markets that are financially sustainable and socially inclusive. This growing interest in agricultural PPPs is driven by results: when done right, they attract private investment and know-how into rural infrastructure while ensuring public goals like food security and inclusion are met. Aninver’s experience in Africa and Latin America has shown that success requires careful feasibility work, stakeholder engagement, and alignment with local needs – all to make sure the PPP isn’t just a fancy label, but a real improvement on the ground.

In conclusion, stripping away the buzzwords means asking the right questions up front: Will farmers or traders be genuinely better off with this PPP? Can the private partner earn a fair return without overburdening users? If the answer is yes, then a PPP can be a powerful vehicle to deliver irrigation networks that keep fields green, cold chain facilities that save harvests from spoilage, and markets that connect producers with prosperity. By focusing on these fundamentals, governments and their partners can ensure that Agri-PPPs deliver tangible benefits – more crops, less waste, and thriving marketplaces – in a financially sound way. And with organizations like Aninver contributing their PPP advisory expertise, such projects are being structured to truly marry profit and purpose, translating high-level concepts into practical, successful development on the ground.