Our Views

Empowering Communities for Climate Resilience: Building Local Capacity to Adapt to Climate Change

Climate change is no longer a distant scenario. It is reshaping daily life through stronger storms, recurring floods, longer droughts, and rising seas—especially in places where public services, infrastructure, and safety nets are limited.

In this context, adaptation cannot be designed only from ministries and headquarters. The most durable resilience is built where impacts happen: in municipalities, cooperatives, community groups, and local value chains.

This article looks at the practical case for locally led resilience and the minimum building blocks that help communities plan, finance, and deliver adaptation that lasts.

Why Local Capacity Matters

Local communities are often the first to face climate shocks and the last to receive support. They understand where water collects, which roads fail first, which crops are most sensitive, and which households are most exposed.

That knowledge is operational. When it is paired with clear decision-making structures and basic tools, communities can anticipate risk rather than only react to disasters.

The challenge is that the enabling environment is still uneven. Funding, data, and authority frequently sit far from the local level. When communities cannot access finance, interpret climate information, or organize implementation, adaptation becomes fragmented and short-lived.

What “Community Capacity” Really Means

Capacity is not just training sessions. It is the combination of skills, systems, and incentives that allow local actors to act consistently over time.

It includes practical capabilities such as conducting a simple vulnerability assessment, maintaining an asset register, managing procurement transparently, and collecting baseline data to track results. It also includes soft infrastructure: trust, participation, and conflict-resolution mechanisms.

Most importantly, local capacity means communities can make trade-offs. When drought hits, they can prioritize water allocation. When storms intensify, they can choose where to rebuild, where to retreat, and where nature-based buffers are more cost-effective than hard infrastructure.

The Minimum Toolkit for Locally Led Resilience

1. Participatory risk planning that produces decisions

Community engagement only matters when it ends with clear choices: which risks are most urgent, which groups need protection, and which investments are realistic.

A good process uses simple mapping, local knowledge, and basic climate information to agree on priority actions. It also clarifies responsibilities between municipalities, utilities, producer organizations, and community committees.

When planning is inclusive and structured, communities buy into difficult measures—like zoning, seasonal access rules, or changes in farming practices—because they understand the logic behind them.

2. Early warning that connects to response

Early warning systems are only “systems” when alerts trigger action. Communities need agreed protocols: who receives alerts, who communicates them, and what households and services do next.

This can be built with low-cost tools—SMS chains, radio announcements, local focal points—if roles are clear and rehearsed. Even basic preparedness reduces losses by protecting assets, livestock, and critical infrastructure.

The key is linking warning to response capacity: evacuation plans, temporary shelters, and simple checklists for schools, clinics, and water points.

3. Climate-smart livelihoods, not just climate-smart projects

Adaptation succeeds when it strengthens livelihoods. In rural areas, climate-smart agriculture often delivers the fastest resilience returns: improved varieties, soil moisture practices, water harvesting, and better extension support.

But the real shift happens when these practices are embedded in value chains. Farmers adopt changes faster when they can access inputs, credit, and stable market linkages—and when risk is reduced through insurance or predictable support programs.

Over time, livelihoods become less dependent on a single climate-sensitive crop or season, which is the foundation of household resilience.

4. Nature-based solutions treated as protective assets

Mangroves, wetlands, reefs, and forests are not “nice-to-have” conservation measures. They function as protective infrastructure that reduces storm impacts, controls erosion, and stabilizes water systems.

Communities can maintain nature-based solutions when governance is practical: clear local rules, incentives for stewardship, and monitoring that is simple enough to sustain.

When designed well, these interventions create local jobs and can support new revenue streams—from eco-tourism to carbon-related mechanisms—while improving physical safety.

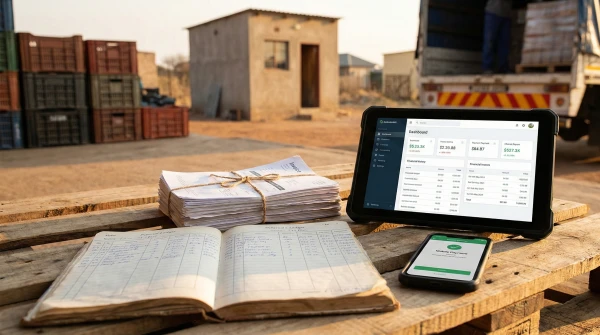

5. Local institutions that can manage money, data, and accountability

The most underestimated part of adaptation is implementation capacity. Local governments and community organizations need basic systems: procurement procedures, reporting templates, grievance channels, and data collection routines.

This is where many good projects fail: not because solutions are wrong, but because there is no structure to deliver them transparently and repeatedly.

Capacity-building works best when it is applied to real tasks—building a baseline, validating beneficiary selection, tracking KPIs—not generic training.

What Works in Practice: Examples You Can Learn From

In landscape and watershed programs, one consistent success factor is local coordination structures that link communities with technical services. When planning units are built around micro-watersheds or catchments, decisions become tangible: where to reforest, where to stabilize slopes, where to protect water sources.

In livelihood-focused resilience programs, success often comes from combining training with access. When farmers have a pathway to inputs, advisory services, and market visibility, adoption accelerates—and practices are maintained after donor funding ends.

In coastal settings, resilience improves when nature-based buffers are connected to governance. Communities protect mangroves and nursery habitats more consistently when rules are enforced locally and benefits (jobs, reduced storm damage, improved fisheries) are visible and shared.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

One frequent pitfall is treating community engagement as consultation rather than co-decision. If people are asked for input but do not see changes, trust erodes and participation drops.

Another is overengineering systems. Local actors do not need complex climate models or heavy reporting frameworks to start. They need usable data, simple tools, and clear roles that can be applied immediately.

A third is underfunding “boring” capacity: baseline data, M&E routines, local procurement support, and institutional strengthening. These are the elements that convert good intentions into durable resilience.

What This Looks Like in Aninver’s Work

In Belize, our work under climate adaptation programs has focused on strengthening implementation quality—not only through technical analysis, but by building the practical foundations that make resilience measurable and equitable. Under the GCF-funded BaC-SuF project, for example, the approach includes vulnerability analysis, transparent beneficiary selection criteria, and a full Monitoring & Evaluation framework supported by baseline assessments. That combination helps ensure that support reaches those most exposed and that results can be tracked in a credible way across the value chain.

Across our climate and resilience portfolio, we see the same principle repeat: communities do not need perfect systems to start adapting, but they do need clear rules, trusted processes, and tools they can actually use. When those elements are in place, adaptation becomes an ongoing capability—not a one-off project.