Our Views

Agriculture in Latin America: The Development Playbook for Productivity, Inclusion, and Climate Resilience

Latin America can feed the world—and in many ways it already does. But the region’s agricultural story is increasingly written by three pressures at once: the need to raise productivity, the urgency to include small producers and rural youth in growth, and the reality that climate volatility is now part of the baseline, not a shock.

What follows is a practical “development playbook” for governments, DFIs, and implementers who want agricultural programs that work in the field, not just on paper. It’s not a silver bullet—more like a set of moves that, combined, consistently improve outcomes.

Start with the real bottleneck: not “production,” but decisions

Many programs begin with inputs: seeds, equipment, subsidized credit. Those can help, but the deepest constraint is often simpler: farmers are forced to make high-stakes decisions with low-quality information. When rainfall shifts, prices swing, pests arrive early, or a buyer changes standards, the difference between coping and losing a season comes down to timely guidance.

That’s why the most effective interventions treat agricultural support as a decision system: advice + follow-up + feedback loops. In practice, this means extension services that are trained, supervised, and measured—not just deployed.

In Panama, for example, Aninver supports the Institute of Agricultural Innovation (IDIAP) under the IDB-financed PIASI program to strengthen assistance to family farmers in Region 1. The work is not only about “more visits”; it’s about how support is delivered, using participatory farm management plans at scale and a Monitoring, Adjustment, and Learning approach so implementation can adapt instead of drifting.

Make productivity inclusive by designing around “the smallholder reality”

“Inclusion” isn’t a side objective; it’s the route to productivity when most producers are small-scale. But inclusion fails when programs assume that smallholders behave like scaled-down commercial farms. They don’t. Their constraints are structural: irregular cashflow, risk aversion because a bad season is catastrophic, limited collateral, and often weak bargaining power in value chains.

A stronger model builds inclusion through three design choices.

First, reduce risk before you ask for investment. Climate-smart practices and productivity upgrades are adopted faster when producers can see short-cycle wins (better post-harvest handling, input timing, basic soil practices) and when the program includes mechanisms for shocks (advisory alerts, contingency planning, flexible repayment where credit exists).

Second, build pathways for youth and women that are economically credible. Not “training for training’s sake,” but training tied to market roles that pay: aggregation, quality control, processing services, digital advisory, logistics, repairs, cold-chain operations, or traceability management.

Third, make producer organizations functional—not symbolic. A cooperative that can actually negotiate, meet standards, and manage payments is a productivity tool. One that only exists to receive a grant is a future headache.

Treat climate resilience as a production input

Climate resilience is often framed as a separate agenda. On the farm, it’s inseparable from productivity. A drought that reduces yields is a productivity problem; a flood that wipes out storage is a competitiveness problem; a heat wave that changes pest dynamics is a management problem.

The playbook move is to embed resilience into day-to-day support: climate-risk farm planning, diversified cropping strategies where feasible, water management, and post-harvest practices that reduce losses. It also means recognizing that resilience investments often need different financing logic than “classic” productivity upgrades, because the returns are partly in avoided losses.

This is where public programs and DFIs can be catalytic: not only funding assets, but funding the “software” that makes assets useful—training, advisory systems, maintenance models, and local capacity. In fragile or drought-prone contexts, Aninver’s work on agriculture, land degradation and fragility in the G5 Sahel reinforced a lesson that also applies in parts of Latin America: resilience gains stick when institutions learn to monitor, adjust, and keep services running under stress.

Build value chains that pay for quality, not just volume

Smallholders don’t scale by producing more of the same. They scale by producing what the market rewards—often quality, reliability, and compliance.

A practical approach is to map value chains with brutal honesty: where is value created, where is it captured, and where is it leaking? In many cases, the biggest gains come from reducing post-harvest losses, stabilizing supply through aggregation, and upgrading basic processing. These are not glamorous interventions, but they move incomes fast.

Done well, value-chain work also creates jobs beyond farming: technicians, packhouse managers, transport coordination, quality inspectors, and digital service providers. That’s how inclusion becomes durable: more roles, more entry points, more local economic circulation.

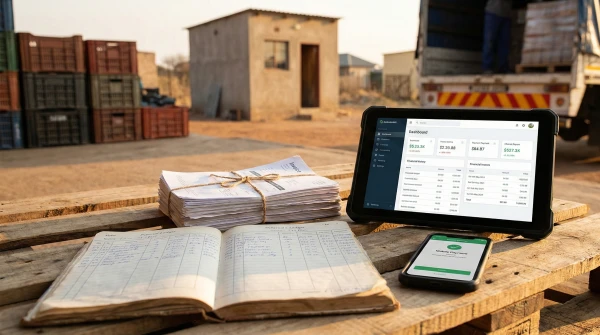

Digitize what matters: “last-mile” systems, not dashboards

Digital agriculture is full of hype. The version that works is quietly practical. It focuses on last-mile execution: how extension agents track visits, how producer plans are registered, how progress is monitored, how alerts reach farmers, and how program managers know what is happening in real time.

Digital tools should reduce friction. If data collection is burdensome, it collapses. If platforms aren’t used by field teams, they become decorative. The target is not a perfect database—it’s a system that helps people do their job better and helps decision-makers course-correct.

In Panama, the emphasis on participatory plans and continuous learning is a good example of digital thinking done right: it’s not tech for optics, it’s tech to make support consistent, traceable, and improvable.

Finance: blend instruments around risk, not ideology

Agriculture finance tends to fail when it’s treated as a single product—“credit.” The smarter playbook blends instruments because constraints differ across producers and across seasons. Some farmers need working capital, others need equipment finance, others need risk coverage or guaranteed offtake terms. Many need technical assistance first, before any loan makes sense.

For governments and DFIs, the opportunity is to fund structures that crowd in finance without pretending agriculture is low-risk. That can mean concessional windows for climate-smart upgrades, guarantees that reduce collateral barriers, or results-based mechanisms that reward verified resilience and productivity outcomes.

Measurement that changes behavior: what you track is what you get

Agricultural projects often measure what is easy, not what is meaningful. Counting trainings is easy. Knowing whether practices changed, yields stabilized, incomes improved, or losses fell—that’s harder, but it’s the whole point.

A good measurement approach is not punitive; it is operational. It creates feedback loops where extension methods, content, and targeting can improve. This is exactly why Monitoring, Adjustment, and Learning systems matter: they make projects adaptive, which is essential when climate and markets refuse to behave.

The “playbook” in one sentence

If you want agriculture programs that deliver productivity with inclusion under climate pressure, design them as service systems (advice + follow-up + learning), connect them to markets that reward quality, and finance them with instruments that respect risk realities instead of ignoring them.

Explore more from Aninver

If you’re interested in how these ideas translate into implementation, you can explore Aninver’s work in family farming technical assistance, results-focused advisory systems, and resilience-oriented rural programming—starting with our ongoing work in Panama supporting IDIAP to strengthen agricultural assistance at scale. We regularly publish practical notes like this one, grounded in project experience and designed for teams building the next generation of rural and agribusiness programs.