Our Views

Regenerative Agriculture in Emerging Economies: Restoring Soils and Enhancing Resilience

Emerging economies are increasingly turning to regenerative agriculture as a practical way to heal degraded lands and build resilience to climate shocks. Instead of pushing soils harder every season, regenerative approaches focus on rebuilding the living foundation that farming depends on: healthy soil structure, biodiversity, and water cycles. In regions such as Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa—where agriculture remains central to rural livelihoods—this shift matters because it can improve productivity without exhausting the resource base.

The pressure on food systems is rising fast. Population growth, volatile weather, and growing competition for land and water mean that “business as usual” often leads to declining fertility, higher input costs, and more risk for farmers. Regenerative agriculture is gaining momentum because it offers a simple proposition: when you restore the soil, you strengthen the entire farm economy—yields become more stable, risks become more manageable, and communities are better equipped to cope with droughts, floods, and market disruption.

What “Regenerative” Really Means

Regenerative agriculture is a way of farming that aims to restore and improve soil health while strengthening the wider ecosystem. It is not one single technique, and it is not a certification label by default. In practice, it is a set of principles that reduce disturbance, keep soils covered, increase diversity, and rebuild organic matter so that land becomes more productive over time—not less.

A key difference from conventional approaches is the mindset. Instead of treating soil as an inert growing medium that must be “corrected” each season with inputs, regenerative farming treats soil as a living system. That system becomes more functional when it is protected and fed—through organic matter, root networks, microbial activity, and stable structure. When it works well, the soil holds water longer, erosion drops, and crops perform better under stress.

The Core Practices, Explained Simply

Most regenerative systems draw from a similar toolbox. The first is reduced tillage. When soils are heavily ploughed, they lose structure and organic matter, and they become more vulnerable to erosion. Reducing disturbance helps keep carbon in the ground and preserves the pore spaces that let water infiltrate instead of running off.

The second is keeping the soil covered as much as possible. Cover crops, mulching, and residue retention protect soils from sun, wind, and heavy rain. They also feed soil biology, which is what keeps nutrients cycling naturally. A covered soil behaves differently: it stays cooler, holds moisture longer, and is less likely to “crust” and compact.

The third is diversity—in rotations, intercropping, and, where possible, integrating trees and livestock. Rotations disrupt pest cycles, improve nutrient balance, and reduce dependency on single crops. Agroforestry and silvopastoral systems add shade, biomass, and root depth, which can transform water management at the field level.

Finally, regenerative farming prioritizes organic inputs and biological fertility. Compost, manure, and green manure crops are not just “fertilizer alternatives”; they rebuild soil organic matter, which is the engine behind long-term productivity. Over time, this can reduce the need for synthetic inputs and make farms less vulnerable to price shocks.

Why It Matters So Much in Emerging Economies

In many emerging economies, the majority of farmers operate with thin margins and limited safety nets. When a drought hits or fertilizer prices spike, the impact is immediate. Regenerative agriculture matters here because it is fundamentally about risk reduction as much as it is about sustainability.

It also fits the realities of smallholder agriculture better than many input-heavy models. When farmers can build fertility locally—through cover crops, composting, better residue use, or tree integration—they become less dependent on external inputs and more able to manage uncertainty. That is especially important where credit access is limited and extension support is overstretched.

There is also a broader development angle. Healthier soils support more stable production, which strengthens local food security and reduces pressure to expand into forests or fragile ecosystems. In the long run, restoring land helps protect water sources, improves biodiversity, and supports rural livelihoods—benefits that go far beyond a single harvest.

Climate Resilience: The Quiet Benefit That Changes Everything

One of the most valuable outcomes of regenerative agriculture is improved water resilience. Healthy soils act like a sponge: they absorb rainfall more effectively and release moisture more slowly. That means farms can withstand dry spells better, and they suffer less damage during heavy rainfall because erosion and runoff are reduced.

This is especially relevant for coastal and tropical climates where rainfall patterns are shifting. As storms become more intense and drought periods more unpredictable, farms that rely on bare soil and heavy tillage become more exposed. Regenerative fields often perform better in these conditions because they are buffered by stronger soil structure, more organic matter, and better ground cover.

Latin America: Productivity, Sustainability, and Market Pull

Latin America has enormous agricultural potential, but it is also dealing with land degradation and rising climate stress. What is changing in the region is that regenerative agriculture is increasingly tied to market incentives and “proof of performance.” Some producers are adopting regenerative practices because they reduce costs and stabilize yields; others are responding to buyers and investors who want evidence of better land stewardship and lower emissions.

In large-scale systems, adoption often starts with no-till, cover crops, and better nutrient management, because these can deliver quick operational gains. Over time, the most durable transitions are the ones that go beyond a checklist and start changing the farm system itself: diversified rotations, integrated livestock, and landscape-level water management.

In smaller-scale systems—particularly in Central America and the Andean region—agroforestry and diversified production models often lead the way. They can improve soils while also adding additional income streams through fruit, timber, honey, or higher-value niche crops. In practice, regenerative agriculture in Latin America is not a single model; it is a spectrum of approaches shaped by farm size, market access, land tenure, and climate risk.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Regeneration as a Livelihood Strategy

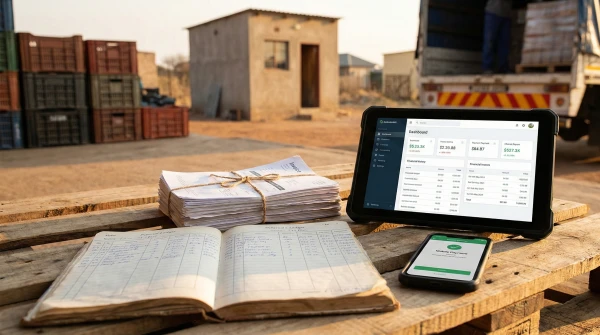

In Sub-Saharan Africa, regenerative agriculture is often less about branding and more about survival and livelihoods. Many farmers are already practicing elements of regeneration—mulching, intercropping, composting, agroforestry—because they have always needed to make the most of limited inputs.

What makes regenerative agriculture powerful in this context is that it can scale through farmer-to-farmer learning and low-cost improvements that build over time. Techniques like natural regeneration of trees, soil and water conservation structures, and diversified cropping systems can restore productivity in areas that were slipping into chronic degradation.

The big challenge is not whether regenerative agriculture works in principle—it is how to make it easier for farmers to adopt at scale. That requires stronger extension services, practical training, access to affordable finance for transition costs, and value chains that reward higher-quality and more resilient production.

What It Takes to Scale: From Projects to Systems

Regenerative agriculture scales when it becomes practical and investable. Farmers need clear guidance on what to do first, how to measure progress, and how to avoid yield dips during transition periods. Governments and development partners can help by strengthening extension systems, supporting seed and input ecosystems for cover crops, and investing in water management, storage, and rural logistics.

Measurement also matters, but it should be realistic. Soil organic matter, ground cover, water infiltration, and yield stability are often more meaningful for farmers than complex carbon accounting. A good scaling strategy prioritizes simple indicators and gradually builds more advanced monitoring where needed.

Finally, scaling depends on markets. When buyers, processors, and financial institutions see regenerative practices as a way to reduce supply risk and improve quality, adoption becomes more attractive. The strongest models connect on-farm practice change with value-chain incentives—so farmers are not asked to do more work for free.

How This Connects to Aninver’s Work

At Aninver, we see regenerative agriculture as a development playbook that connects productivity, inclusion, and climate resilience. Across agriculture-focused assignments, the lesson is consistent: soil restoration works best when it is paired with practical delivery systems—extension support, farmer training, workable monitoring, and value-chain improvements that make resilience pay.

If you would like to explore how this thinking translates into real programmes—especially in rural development, value chains, and climate-smart agriculture—we invite you to discover more about Aninver’s work and insights through our projects and publications.