Our Views

PPP Projects Need Marketing Too: Attract Bidders and Investors Before the Tender

A lot of PPPs fail long before the tender is even published.

Not because the project is inherently “bad,” but because the market never really understood it: what the government is trying to achieve, how key risks will be handled, and whether the procurement will be fair, predictable, and genuinely bankable. When that understanding is missing, the symptoms are familiar—thin competition, inflated pricing, early interest that disappears later, and a process that drags on until politics or budgets quietly pull the plug.

That’s why PPPs need marketing.

Not glossy brochures or hype. Structured market engagement that reduces uncertainty, builds confidence, and helps serious bidders decide—early—that the project is worth their time and bid costs.

This article is a practical guide for public sector teams that want to attract credible bidders and investors before the tender clock starts—without compromising transparency or giving anyone an unfair advantage.

What “marketing” means in a PPP context

In PPPs, marketing isn’t selling. It’s risk reduction.

Before a consortium commits internal resources, it usually tries to answer three simple questions:

- Is the project real? Meaning: political commitment is stable, approvals are progressing, funding is credible, and the timeline is believable.

- Is it bankable? Meaning: the risk allocation, revenue model, and contract approach can actually be financed in the real world.

- Is the process credible? Meaning: the procurement will be transparent, rules will be consistent, and the information base will be strong enough to price with confidence.

Pre-tender communication should consistently address those questions—with evidence, not promises.

Start with the basics: make the project “legible” to the market

Many public teams jump straight into procurement documentation. But long before a bidder reads the draft contract, they need a simple, coherent picture of what they are being asked to deliver.

At minimum, the project needs to be easy to explain in plain language: what problem it solves, what service standard is expected, how performance will be measured, how the private partner gets paid (user-pay, availability, or hybrid), what the high-level risk allocation looks like, and what the key milestones and decision gates are.

A useful test is brutally simple: if you can’t explain the project in two pages, the market will assume the worst—and price for it.

A practical trick is to draft a one-page “investment narrative” a bidder could forward internally to an investment committee. If it reads like government jargon, you’ve already lost attention—often before the bid is even considered.

Do market sounding early, and treat it like intelligence—not a ceremony

Market sounding shouldn’t be a box-ticking consultation. Done well, it is one of the highest-return steps in PPP preparation, because it tells you—early—where the market will struggle and where it will price risk aggressively.

The point is not to “sell” the project. The point is to pressure-test your assumptions:

- Are contract terms realistic for the sector?

- Is the risk allocation financeable?

- Are there enough capable operators and EPCs likely to compete?

- What red flags might trigger no-bids or conservative pricing?

The value is not in having meetings—it’s in asking comparable questions, capturing patterns, and making adjustments that bidders can later see reflected in the documents. If market sounding happens and nothing changes, the market remembers. Next time, serious players often won’t bother engaging.

Make bankability visible early—before lenders “discover surprises” later

Bidders don’t only compete with each other. They compete for debt approvals, guarantees, and equity sign-off. When lenders see ambiguity, they add conservatism—and that conservatism shows up as higher unitary payments, higher tariffs, or tougher contractual positions.

Pre-tender, you want to demonstrate that the public sector understands and is managing the bankability essentials: land and permitting strategy, ESG and safeguards pathway, the insurance approach, indexation and inflation logic, termination and compensation principles, dispute resolution, and step-in rights.

You don’t need to finalize every detail before procurement. But you do need to show that these issues won’t be “discovered” halfway through the process.

This is where a pre-tender data-room mindset already matters. Even early numbers and assumptions should be traceable, consistent, and defensible. When bidders can follow the logic, they price with confidence instead of padding contingencies.

Don’t just publish documents—build trust through predictability

The best way to attract high-quality bidders is to be boring in the right way.

Markets reward authorities that stick to timelines, answer questions clearly, treat all bidders equally, and avoid late surprises. This is the hidden power of communications planning: it’s not PR, it’s process credibility.

One strong practice is to publish a procurement communications protocol upfront—how questions will be handled, how clarifications will be issued, and how changes will be managed. Serious bidders notice this because it reduces their internal risk when they ask for approval to spend serious money on the bid.

Reduce the “silent dealbreakers” that make bidders disappear

Often, bidders won’t tell you why they’re not bidding. They simply don’t show up.

The most common silent dealbreakers are rarely ideological—they’re practical: unclear land acquisition responsibilities, untested demand assumptions, under-specified service standards, political risk with no mitigation, unrealistic construction timelines, or a payment mechanism that doesn’t match sector reality.

The solution is to stress-test these issues early and address them openly. Hoping uncertainty won’t matter almost never works. The market prices ambiguity whether you acknowledge it or not.

Use pre-tender visibility to build a pipeline—not just one transaction

The strongest PPP markets weren’t built by luck. They were built through a pipeline.

If the private sector believes the government will do one PPP and then disappear, the incentive to invest in learning your approach drops sharply. But when bidders see a credible forward calendar, they’re more willing to build teams, understand your model, and compete seriously.

Even if the pipeline is small, communicate it. The message is simple: this isn’t a one-off. If you invest in understanding us, there will be future opportunities.

How to do this without compromising fairness

A common concern is that market engagement creates an unfair advantage. It doesn’t have to.

A safe, standard approach is straightforward: engage widely rather than selectively, document what you hear, publish key clarifications and decisions, and ensure tender documents contain the same information for everyone. When engagement is needed, structure it through open investor days, published Q&A logs, and standard templates for feedback submission.

The goal is equal access to information—not equal access to meetings.

The pre-tender “marketing pack” that actually works

A strong pre-tender pack is not a glossy pitch deck. It’s a coherent story, backed by usable facts.

At its best, it explains the project in plain language, outlines the payment mechanism and high-level risk allocation, confirms the status of land and permits, shares an early technical concept and service standards, and provides initial demand or revenue logic with clearly stated assumptions. It also sets out governance, timeline, and how transparency will be protected throughout procurement.

Most importantly, it feels grounded and honest about what is still being defined. Over-promising is worse than saying, clearly: “this element is still under development, and here is the path to finalization.”

Where we’ve seen this make the biggest difference

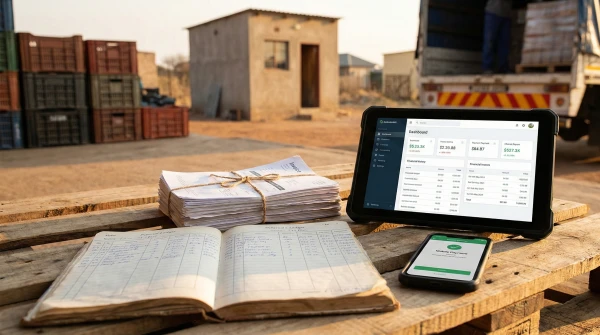

In practice, PPPs that attract serious bidders early tend to share one pattern: they have done the unglamorous work of clarifying risks and making data usable.

Across PPP assignments—whether supporting early structuring, reviewing pre-feasibility outputs, or advising on specialized components like tax, insurance, and risk allocation—we repeatedly see the same dynamic. When the public sector explains assumptions, defines responsibilities, and shows evidence of preparation, bidders spend their energy optimizing solutions rather than protecting themselves with contingencies.

And when bidders price with confidence, governments usually get what they want most: stronger competition, better value for money, and fewer disputes after signature.