Our Views

Sustainable Fisheries Management: Balancing Conservation and Livelihoods in Developing Countries

Small-scale fisheries are the backbone of coastal life in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. In many developing countries, fishing is not only a job but a daily source of food security, income, and identity for millions of households. Yet these fisheries often operate under pressure: stocks decline, habitats degrade, and informal markets keep earnings low even when effort is high.

The real challenge is not choosing between conservation and livelihoods. It is designing systems where healthy ecosystems support stable catches and where fishing communities have a fair chance to earn a living without exhausting the resource. That balance is possible, but it requires clear rules, usable data, and institutions that communities trust.

For too long, conservation was treated as restriction and livelihoods as extraction. The more practical view is that both depend on the same thing: a fishery that can reproduce, recover, and withstand shocks. Below, we unpack five approaches that are increasingly used together—marine spatial planning, co-management, rights-based tools, value chain strengthening, and climate resilience—plus what we have learned from related work in the Blue Economy space.

Marine Spatial Planning: Making the Ocean Legible

Coastal waters are no longer “just fishing grounds.” They are shared spaces for tourism, shipping, energy, conservation, and community use. Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) helps governments map these uses and make deliberate choices about where activities should happen, and under what rules.

In practice, MSP is less about drawing lines on a map and more about reducing conflict and uncertainty. When small-scale fishers know which zones protect nursery habitats, where industrial fleets cannot enter, and which areas are reserved for community use, compliance becomes more realistic and disputes reduce. Equally, when investors in ports or tourism can see clear spatial rules, development becomes less disruptive.

The most important ingredient is participation. MSP works when fishing communities, local authorities, scientists, and private operators can negotiate trade-offs using shared information. When done well, it becomes a platform for balancing ecosystem protection with sustainable economic activity—especially where the coast is changing fast.

Co-Management: Turning Rules Into Ownership

Central ministries rarely have enough boats, staff, or credibility to enforce fisheries rules alone. Co-management fills that gap by sharing responsibilities between public authorities and local fishing groups—so decisions are not only imposed, but co-owned.

The value of co-management is practical. Local actors know seasons, gear patterns, landing sites, and informal routes that do not show up in official statistics. When this knowledge is integrated into closed seasons, gear restrictions, or local protected areas, the rules fit reality—and therefore stand a higher chance of being respected.

Co-management also helps solve a trust problem. Communities are far more likely to accept limits when they see how decisions were made, who benefits, and how enforcement is applied. The result is often less “policing” and more shared stewardship, with better outcomes for both stock recovery and social stability.

Rights-Based Fisheries: Incentives That Last Longer Than a Season

Open-access fisheries often trigger a race: if you do not catch the fish today, someone else will tomorrow. Rights-based approaches try to replace that race with long-term thinking by assigning fishing rights to people, cooperatives, or communities—whether through quotas, territorial rights, or limited entry systems.

The goal is not privatization for its own sake. It is predictability. When fishers have secure access, they can plan investments, adopt better practices, and support restrictions that rebuild stocks because they know benefits will return to them rather than being captured by outsiders.

These systems need careful safeguards. Without transparent allocation rules, rights can be captured by elites or transferred away from communities. But when designed with clear eligibility criteria, monitoring, and dispute resolution, rights-based tools can stabilize effort and create the incentive structure that sustainability depends on.

Value Chain Strengthening: Earning More Without Catching More

Even well-managed fisheries can fail communities if value chains stay weak. In many coastal economies, fishers lose income through post-harvest losses, poor storage, lack of market information, and dependence on middlemen. The outcome is painful: people work harder for smaller margins, which increases pressure on the resource.

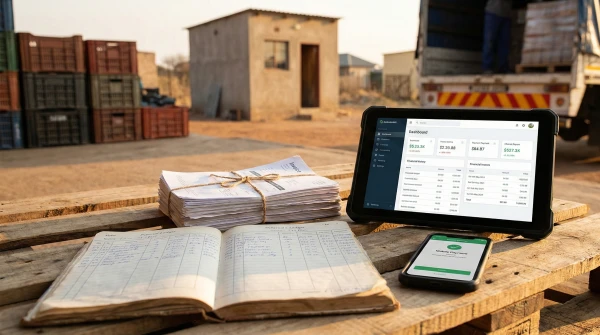

Value chain strengthening is how you shift that equation. Cold storage, ice plants, improved landing sites, and basic quality standards can reduce spoilage and raise prices. Training and micro-finance can help cooperatives upgrade processing and packaging, while digital tools can improve traceability and connect fishers to buyers beyond local gatekeepers.

This matters for sustainability because it changes incentives. If communities can earn more per kilogram through better handling, smarter logistics, and stronger bargaining power, they do not need to chase volume to survive. It is one of the most direct ways to align livelihood improvement with conservation.

Climate Resilience: When the Fish Move and the Coast Changes

Climate change is reshaping fisheries faster than many management systems can adapt. Warming waters, coral bleaching, shifting currents, and extreme storms alter where fish live, when they spawn, and whether communities can safely fish at all. For small-scale operators with limited assets, climate risk becomes a daily constraint.

Building resilience starts with ecosystems. Mangroves, seagrasses, and reefs are not “nice to have”—they protect coastlines and provide nursery habitat that sustains stocks. Resilient fisheries management increasingly pairs conservation with practical adaptation: early warning systems, safer landing infrastructure, diversified livelihoods, and flexible rules that can adjust as species distribution changes.

The most resilient approaches also broaden the development lens. Fisheries policy can no longer sit alone; it must connect to coastal planning, disaster risk management, and finance. When governments treat climate impacts as core operational risks—not future scenarios—investment decisions become smarter and communities become safer.

What This Looks Like in Practice: A Blue Economy Lens

Across Blue Economy work, we often see the same pattern: the most durable solutions are those that combine governance, economics, and ecology rather than treating them separately. Fisheries improve when spatial planning clarifies “where,” co-management strengthens “who decides,” value chains improve “how people earn,” and climate resilience defines “how the system survives shocks.”

That is why sustainable fisheries management is not a single instrument. It is a portfolio. Countries that succeed tend to apply several tools at once, starting with the basics—data that communities recognize as credible, rules that match local reality, and enforcement that is fair.

Where This Connects to Aninver’s Work

At Aninver, we see sustainable fisheries management as a core piece of wider Blue Economy strategies. In Belize, for example, our work has supported the development of an integrated Blue Economy approach that brings together fisheries, aquaculture, coastal and marine tourism, and conservation—so that growth plans do not undermine the ecosystems they rely on.

In West Africa, including Benin, our experience has reinforced how often the bottleneck is not willingness but systems: fragmented institutions, weak value chains, and limited tools to translate policy into implementation. That is why our work frequently focuses on diagnostics, stakeholder engagement, and practical roadmaps—helping public institutions and partners move from ambition to action, with fisheries managed as both a livelihood sector and a natural asset base.

Sustainable fisheries management is ultimately a governance and development project as much as an environmental one. When countries invest in the right mix of planning, incentives, value chain upgrades, and resilience, they protect ecosystems while strengthening the livelihoods that depend on them—and that is the balance the Blue Economy is meant to deliver.